s you walk around the walls of Chester, leaving the River Dee,

crossing busy Grosvenor Road and entering Nun's Road, on the left you can see

the great green expanse of the Roodee,

the city's ancient racecourse, and on the right, the vast, and brand new, HQ Building, a development of apartments, offices and hotel that has recently risen upon the site of the Cheshire Police Headquarters building. Pictures of the old and new buildings may be seen on the first of our Roodee pages. s you walk around the walls of Chester, leaving the River Dee,

crossing busy Grosvenor Road and entering Nun's Road, on the left you can see

the great green expanse of the Roodee,

the city's ancient racecourse, and on the right, the vast, and brand new, HQ Building, a development of apartments, offices and hotel that has recently risen upon the site of the Cheshire Police Headquarters building. Pictures of the old and new buildings may be seen on the first of our Roodee pages.

It is difficult to imagine how this area would have looked hundreds of years

ago, when of Mammon there was no trace and all the vast area on your right hand side, right as far as the Infirmary at the far end of the road, was entirely occupied by Chester's religious

houses: the monasteries of the White, Black and Greyfriars and, immediately

on our right, the convent and gardens of the Nuns of St. Mary's, whose lands extended from

the arch in the wall near the Castle to Blackfriars, the narrow thoroughfare known in earlier times as Arderne Lane and later

as Walls Lane.

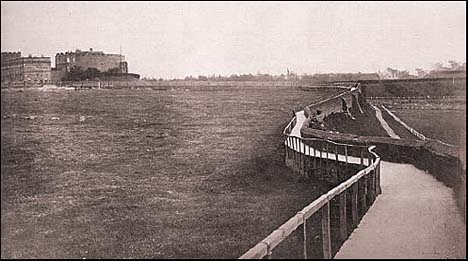

Even a century or so ago, things looked very different

from today, as you see in this fascinating old photograph, showing a view quite alien even to those who know the area well today. On the right, the Roodee

and the great man-made embankment leading to the Grosvenor Bridge are much as we know them now, but nothing at all lies between the City Wall and the distant Castle and the grand Militia Buildings- which stood on the exact site of the modern complex above. All trace of the nun's estates, which thrived here for four centuries, have vanished as if they had never been.

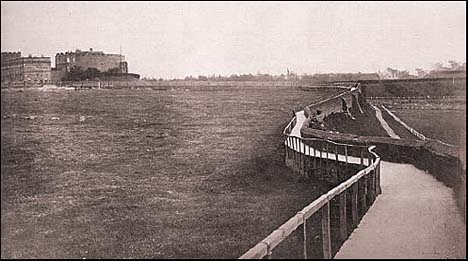

Below, we see a slightly later view, looking in the opposite direction. Villas have started to rise but Nun's Road is yet to appear and its site is still an uneven grassy

track snaking its way along the top of the City Wall. Below, we see a slightly later view, looking in the opposite direction. Villas have started to rise but Nun's Road is yet to appear and its site is still an uneven grassy

track snaking its way along the top of the City Wall.

The entire area west of the present-day Inner Ring Road was enclosed within

the enlarged circuit of the walls by the Saxons in the early 10th century,

but long remained as open ground. It was occupied by the churches and cloisters

of religious communities commencing sometime in the 12th century, and possibly

earlier. Even so, the majority of the land remained unbuilt-upon, serving

as the fields and vegetable gardens of the monks and nuns. These fields, which

became known as The Crofts, after the dissolution of the monasteries

in the 1530s and 40s, were gradually developed- the final section, Lady

Barrow's Hey, at the far end of the road, as late as 1963, when the site

was occupied by the extension of the Infirmary, which itself was demolished

in 1998 to make way for new housing.

The earliest charter connected with the nunnery we know of dates from about

the year 1150, though it is known the nuns were in Chester before that date,

possibly at another site. It says:

"Randulph, Earl of Chester, etc., grants to God and St. Mary and the nuns

of Chester, those crofts which Hugh, son of Oliver, held of the demesne of

the grantor, with the goodwill of the said Hugh, who has quit-claimed them

before grantor and his Countess, etc., towards the building there of a church

in honour of God and Saint Mary, for the remission of grantor's sins, etc.,

and for the founding of their building. Witnesses: John and Roger, chaplains,

Matilda the Countess, Hugh the Earl's son, Fulk de Brichsard, Ralph Mansell,

Richard the butler; at Chester." "Randulph, Earl of Chester, etc., grants to God and St. Mary and the nuns

of Chester, those crofts which Hugh, son of Oliver, held of the demesne of

the grantor, with the goodwill of the said Hugh, who has quit-claimed them

before grantor and his Countess, etc., towards the building there of a church

in honour of God and Saint Mary, for the remission of grantor's sins, etc.,

and for the founding of their building. Witnesses: John and Roger, chaplains,

Matilda the Countess, Hugh the Earl's son, Fulk de Brichsard, Ralph Mansell,

Richard the butler; at Chester."

This grant of land, free from toll and tax, was soon followed by others, including

an area across the river at Handbridge known as Geffreis' Halgh (or 'sloping

ground') which is thought to be the areas now ocupied by the Overleigh Cemetery and Edgar's

Field.

Also across the river, in a field known as Kettle's Croft they

had a chapel known as Little St. Mary's, the greater part of which was eventually,

long after the Dissolution, carried away by a flood. Randulph granted the

nuns permission to have one boat on the Dee, and to fish with one net, whenever

they chose.

Around the year 1160, two separate charters brought St. Mary's a large amount of land in Christleton, a village not far from Chester. Despite this, less than 100 years later, in 1253, the financial state of the nunnery was at such a low ebb that the Prioress, Lady Alice de la Hey, petitioned Queen Eleanor ('Eleanor of Provence'), wife of Henry III, giving a pitiable account of their condition. She stated that they were "So greatly reduced as to be compelled every day to beg for their food abroad- slight as even that was."

As a result, gifts were freely showered upon the nunnery, and it became possessed of great wealth and power, owning property in most of the streets of Chester as well as land in Cheshire, Lancashire and even as far as South Wales.

In 1185, Earl Randle Blundeville granted to the nuns the small manor of Wallerscote in Delamere Forest, a few miles from Chester. They held this until the Dissolution and by virtue of it had rights of pasture in the forest. In 1185, Earl Randle Blundeville granted to the nuns the small manor of Wallerscote in Delamere Forest, a few miles from Chester. They held this until the Dissolution and by virtue of it had rights of pasture in the forest.

The Prioress held her own court which was composed of all her tenants in the

manors of Honnebrugge (Handbridge) and Chester. Edward, the Black Prince granted the nuns (and their tenants) exemption from serving on juries and

inquisitions, and from various taxes, including murage, and they were entitled

to supplies of timber from the Royal park of Shotwick, for fuel and building

purposes. The nuns also had the right to have their corn ground free of charge

at the Dee Mills.

In the year 1281, in order to gain access to the river, the nuns were granted charters that stated:

1. "A free exit of the water from their garden, by the middle of the land which Philip the Clerk, citzen of Chester, had under the wall of the city, opposite the water of Dee, by the garden of Robert Mercener, so that he and his heirs incurred no damage and were not hindered in ploughing and sowing."

2. "A way across the croft which the same Philip the clerk had, under the wall of the city, opposite the water of Dee, by the Quarry, to be eight feet in breadth outside the ditch by his garden, and to extend to the wall of the city to Eya- that is, the Roodee."

In 1353, the Prioress, Helewysca, was charged with obstructing the high-road on the walls opposite the nunnery, with a bolted door, to the prejudice of the city liberties.

When the end came, with the Dissolution in 1537, and the nunnery was handed over to the agents of Henry VIII, the last Prioress, Elizabeth Grosvenor, was granted a pension of £20 and eleven other nuns received pensions ranging from 26s 8d to £4- which they are recorded as continuing to receive in 1556, twenty-one years later. When the end came, with the Dissolution in 1537, and the nunnery was handed over to the agents of Henry VIII, the last Prioress, Elizabeth Grosvenor, was granted a pension of £20 and eleven other nuns received pensions ranging from 26s 8d to £4- which they are recorded as continuing to receive in 1556, twenty-one years later.

In 1541, the buildings and land were granted to Urian Brereton the Elder and Urian his son, who remarkably managed to obtain the same privileges regarding freedom from taxes, etc., that had been enjoyed by the nuns. This was fiercely opposed by the city authorities and resulted in years of argument and litigation. The former nunnery buildings continued to be used as one of the residences

of the Breretons up to and including Sir William Brereton, commander

of the Parliamentary forces besieging Chester during the Civil War, until

they were looted and destroyed by the Royalist occupants of the city. The

site seems to have then lain derelict and the stones removed for use elsewhere.

Two arches survived which remained in situ for many years,

until the eastern one was removed, around 1783 to form an entrance to the

ruins at St. John's Church from where

it was moved again in 1871 to the position it has since occupied in Grosvenor

Park, as illustrated in the photograph above.

(A fate shared by the ancient Shipgate- which

formerly stood by the riverside close to the Bridgegate- whose semi-circular arch you can see in the background).

Here we see the ruins still in place, as recorded by the eminent artist George Cuitt (1779-1854) in 1827. Opposite stands the grand entrance or Propylaeum of Thomas Harrison's re-built Castle, erected just 12 years earlier. Here we see the ruins still in place, as recorded by the eminent artist George Cuitt (1779-1854) in 1827. Opposite stands the grand entrance or Propylaeum of Thomas Harrison's re-built Castle, erected just 12 years earlier.

In

1831, Chester

guide

and

author Joseph Hemingway wrote of this western arch, "The pointed arch... was in existence some few years ago, which stood in the middle of a plot of ground called the Nun's Gardens, now an enclosed field in front of Mr. Harrison's house, but no vestige of it now remains."

(The great Chester architect Thomas Harrison had, late in life- around 1820, moved from Folliot House in Northgate Street to a new house here, designed by himself, and situated close to his great Grosvenor Bridge project. This was St. Martin's Lodge, a simple and elegant, understated piece of Regency architecture, which remains with us today and, until their neighbouring HQ was demolished, was utilised for administative purposes by Cheshire Police.

It was long in poor condition, boarded up and its front garden used for car parking. However, in 2011 the property was acquired for something in the region of £1 million by a pub/restaurant company and at the time of this most recent update- December 2012- its conversion into a pub by the name of 'The Architect' is approaching completion. Our pictures show the house as it looked in 2010 and, below, newly-built in 1825.

Eighty years later, in 1910, Chester historian Frank Simpson wrote that, "The arch was in situ as late as 1827, but one has yet to discover when it was taken down and to what place it was removed."

The anonymous author of an early 19th century work, A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, wrote of the nun's house, "The church was twenty-two yards long and fifteen broad, and supported in the middle by a row of pillars. The Chapel was nine yards by four and three quarters; the cloisters thirty yards by twenty. Vestiges of the walls and arches are yet remaining. In 1805 a Roman tesserated pavement was discovered and may be seen in the gardener's house." The anonymous author of an early 19th century work, A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, wrote of the nun's house, "The church was twenty-two yards long and fifteen broad, and supported in the middle by a row of pillars. The Chapel was nine yards by four and three quarters; the cloisters thirty yards by twenty. Vestiges of the walls and arches are yet remaining. In 1805 a Roman tesserated pavement was discovered and may be seen in the gardener's house."

Needless to say, the whereabouts of this ancient relic is unknown today! Needless to say, the whereabouts of this ancient relic is unknown today!

In 1854-6 arose on the site the castle-like Militia Buildings which were constructed just after the Crimea War and were used as married quarters for the families of troops serving at Chester Castle. You can see some photographs of them here.

Had they survived, the old Militia Buildings would doubtless now be in demand for conversion into apartments or the like, but, as we heard in the Roodee section of our Virtual Stroll, they were sadly demolished to make way for the exceedingly ugly and inappropriately-sited County Police Headquarters, which was built here between 1964 and 1967- and in turn demolished in October 2006.

Before the Police HQ was built, a hurried archaeological excavation of the site was

allowed, when the foundations of the nun's church, measuring 22 yards by 15 yards,

their cloisters and other buildings were identified and mapped. What further relics may come to light before new buildings arise on the site only time will tell...

Well, in 2008/9 as new archaeological investigation did happen and, we're told, all manner of interesting relics of the old nunnery came to light, including their graveyard. This beautifully-carved coffin lid from the site is now on public display outside the new HQ develpment. The high quality of the workmanship would seem to indicate that an important member of this lost relgious community once lay beneath this stone.

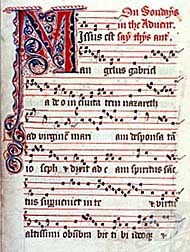

Though the nuns of St. Mary's are centuries dead and their bones and the stones of their house are scattered and lost, a part of them remains with us today, for, around the year 1425 was composed within the walls of the nunnery the beautiful Carol (or Song) of the Nuns of Chester which forms part of the repertoire of choirs throughout the world and is widely available in numerous recordings. This beautiful carol is a combination of an old Latin hymn (Qui Creavit Caelum), with a lullaby verse after each line:

The Lord who created the heavens,

Lully lully lu;

Is born in a stable,

Byby byby by,

The King of all mankind,

Lully lully lu.

Between two animals

Byby byby by,

Lies the Joy of the world,

Lully lully lu,

Sweet beyond anything,

Byby byby by |

|

|

This lovely Latin lullaby utilized by the sisters is one of the typical carols of late medieval England. Yet, by a century or so later the traits which made it typical, that is, the Latin language, strong religious content, and connection with the Catholic Church, had largely disappeared. It is one of the last Latin carols written in England. A distinguished contemporary, “There Is No Rose of Such Virtue,” had already abandoned Latin for English. Even in the still-medieval fifteenth century songs such as "The Boar’s Head Carol” had mostly non-religious lyrics and by the sixteenth-century highly secular carols such as “We Wsh You a Merry Christmas” became commonplace throughout the British Isles. In addition, Henry VIII’s break with Rome in 1534 greatly diminished the influence of the Catholic Church in England. Thus the “Song of the Nuns of Chester” is in some ways the benchmark of the passing of an era. But lest we mourn too much, the period which succeeded it was the English Renaissance, the greatest cultural epoch in the history of that nation and also the golden age of the English carol. |

s you walk around the walls of Chester, leaving the River Dee,

crossing busy Grosvenor Road and entering Nun's Road, on the left you can see

the great green expanse of the Roodee,

the city's ancient racecourse, and on the right, the vast, and brand new, HQ Building, a development of apartments, offices and hotel that has recently risen upon the site of the Cheshire Police Headquarters building. Pictures of the old and new buildings may be seen on the first of our Roodee pages.

s you walk around the walls of Chester, leaving the River Dee,

crossing busy Grosvenor Road and entering Nun's Road, on the left you can see

the great green expanse of the Roodee,

the city's ancient racecourse, and on the right, the vast, and brand new, HQ Building, a development of apartments, offices and hotel that has recently risen upon the site of the Cheshire Police Headquarters building. Pictures of the old and new buildings may be seen on the first of our Roodee pages. Below, we see a slightly later view, looking in the opposite direction. Villas have started to rise but Nun's Road is yet to appear and its site is still an uneven grassy

track snaking its way along the top of the City Wall.

Below, we see a slightly later view, looking in the opposite direction. Villas have started to rise but Nun's Road is yet to appear and its site is still an uneven grassy

track snaking its way along the top of the City Wall. "Randulph, Earl of Chester, etc., grants to God and St. Mary and the nuns

of Chester, those crofts which Hugh, son of Oliver, held of the demesne of

the grantor, with the goodwill of the said Hugh, who has quit-claimed them

before grantor and his Countess, etc., towards the building there of a church

in honour of God and Saint Mary, for the remission of grantor's sins, etc.,

and for the founding of their building. Witnesses: John and Roger, chaplains,

Matilda the Countess, Hugh the Earl's son, Fulk de Brichsard, Ralph Mansell,

Richard the butler; at Chester."

"Randulph, Earl of Chester, etc., grants to God and St. Mary and the nuns

of Chester, those crofts which Hugh, son of Oliver, held of the demesne of

the grantor, with the goodwill of the said Hugh, who has quit-claimed them

before grantor and his Countess, etc., towards the building there of a church

in honour of God and Saint Mary, for the remission of grantor's sins, etc.,

and for the founding of their building. Witnesses: John and Roger, chaplains,

Matilda the Countess, Hugh the Earl's son, Fulk de Brichsard, Ralph Mansell,

Richard the butler; at Chester."  In 1185, Earl Randle Blundeville granted to the nuns the small manor of Wallerscote in

In 1185, Earl Randle Blundeville granted to the nuns the small manor of Wallerscote in

The anonymous author of an early 19th century work, A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, wrote of the nun's house, "The church was twenty-two yards long and fifteen broad, and supported in the middle by a row of pillars. The Chapel was nine yards by four and three quarters; the cloisters thirty yards by twenty. Vestiges of the walls and arches are yet remaining. In 1805 a Roman tesserated pavement was discovered and may be seen in the gardener's house."

The anonymous author of an early 19th century work, A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, wrote of the nun's house, "The church was twenty-two yards long and fifteen broad, and supported in the middle by a row of pillars. The Chapel was nine yards by four and three quarters; the cloisters thirty yards by twenty. Vestiges of the walls and arches are yet remaining. In 1805 a Roman tesserated pavement was discovered and may be seen in the gardener's house." Needless to say, the whereabouts of this ancient relic is unknown today!

Needless to say, the whereabouts of this ancient relic is unknown today!