|

eyond

the sorry remains of the amphitheatre,

through

a screen

of

trees, you

can

see

what

is,

at

first

glance,

a rather

unprepossessing,

Victorian-style

sandstone

church.

In

fact,

this

is

the

ancient

and

unique Church

of

St. John

the

Baptist-

a surviving portion of what was once a much grander building which served for a time as Chester's

first cathedral at a period when our present cathedral was still a Benedictine abbey. eyond

the sorry remains of the amphitheatre,

through

a screen

of

trees, you

can

see

what

is,

at

first

glance,

a rather

unprepossessing,

Victorian-style

sandstone

church.

In

fact,

this

is

the

ancient

and

unique Church

of

St. John

the

Baptist-

a surviving portion of what was once a much grander building which served for a time as Chester's

first cathedral at a period when our present cathedral was still a Benedictine abbey.

This beautiful painting

by an unknown artist illustrates how the church appeared in the middle of the 19th century and its dramatic location on a sandstone plateau high above the waters of the River Dee.

In the foreground is the 14th century (but standing on the site of several predecessors and a Roman original) Old Dee Bridge looking much as we know it today and the land where cattle are grazing, known as Edgar's Field, is now a charming public park in the suburb of Handbridge.

The venerable church's appearance is now very different; as we shall discover, as that tall Gothic tower collapsed on Good Friday 1881 and later buildings and tall trees in the churchyard and by the river now obscure the lower parts.

Nothing is certain regarding the origins of buildings of such antiquity but it is recorded that the

Saxon

church

that

first stood

on

this

site

was founded

by King

Aethelred

of

Mercia in

about

the year

689.

Did the site follow the common practice of being previously revered by people of an earlier time? Did our Roman founders, influenced by their equally-Pagan predecessors, erect one of their temples on this spot overlooking the sacred waters of Deva? We may never know. Legend, however,

tells

how

Aethelred

had a dream, in which he was instructed by God

to

build

a church "at the place where he sees a white hind" (a beast symbolic of Christ and his presence on earth). When later out hunting- the forest then approached close to the City Walls, indeed, Foregate Street outside the Eastgate was once known as Forest Street- the etherial creature was indeed seen by the King at this spot and his church duly built.

The

Chester

monk

Henry

Bradshaw

(d.1513)

in

his Lyfe

and

History

of

St. Werburghe wrote

as follows regarding

the

church's

founding:

The yere of Grace syxe hundreth foure score and nyen,

As sheweth myne auctour a Bryton Giraldus, Kynge Ethelred,

myndynge most the blysse of Heven,

Edyfyed a College Church notable and famous,

In the suburbs of chester, pleasant and beautious,

In the honour of God, and the Baptyste Saynte John,

With help of bysshop Wulprye, and good exortacions. |

A later

Aethelred-

Earl

of

Mercia

and

husband

of Aethelflaed,

'Lady of the Mercians' and daughter

of Alfred

the

Great-

rebuilt

and

enlarged

the

church

in

the

early

10th

century,

as

part

of

their

restoration

of

the

(possibly) abandoned

Roman

fortress, the radical enlagement of its walls

and

establishing it

as

the

centre

of

a long line

of burghs to

protect

the

northern

frontier

of

Mercia from the Danes-

the

true

founding

of

the

City

of

Chester.

They

rededicated

St. Peter

and

Paul's

Church,

on

the

site

of

the

present Cathedral,

to St. Werburgh. (To keep them safe from the invaders, Werburgh's bones had been carried by the nuns from Hanbury to the safety of the stronghold of Chester where they

were

buried

in

875). They

transferred

the

old

dedication

to

a new

church

in

the

town,

today

still

known

as St. Peter's,

at

the

High

Cross.

In

1066,

St. John's

had

formed

part

of

the

Saxon

manor

of Radeclive (Redcliff)

after

the

colour

of

the

local

sandstone

which

was

quarried

to

the

south

of

the

church. In

1066,

St. John's

had

formed

part

of

the

Saxon

manor

of Radeclive (Redcliff)

after

the

colour

of

the

local

sandstone

which

was

quarried

to

the

south

of

the

church.

In

1862,

fourty

Saxon

coins

of

the

reign

of Edward

the

Elder (ruled

899-925)

were

found

buried

deep

beneath

the

church

and

some

fine

Saxon

crosses

from

the

same

period

unearthed

here

are

displayed

within.

Within

a decade

of

the

arrival

of

the

Normans

(Chester was the last city in England to fall to them, in

1069,

a full

three

years

after

the

Battle

of

Hastings) Peter

de

Leia, Bishop

of

Lichfield-

head

of

a vast

diocese,

extending

from

the

Trent

to

the

Solway

and

comprising

most

of

the

former

Saxon

Kingdom

of

Mercia-

transferred

his

see

from

Lichfield, "then

a sordid

and

desert

place"

to

Chester,

"a

city

of

reknown".

This

was

the

result

of

an

order

that

Bishops

should

reside

in

the

cities

of

greatest

importance

within

their

respective

dioceses.

In

1075,

he

proceeded

to

erect

a great

cathedral

on

the

site

occupied

by

Aethelred's

humble

church.

Why

the

Bishop

chose,

in

those

warlike

and

unruly

times,

a site

outside

the

safety

of

the

City

Walls

we

do

not

know.

Perhaps

it

was

the

centuries-old

sanctity

of

the

place

that

attracted

him-

or

it

may

be

that

he

was

unable

to

secure

a site

large

enough

for

his

grand

plan

within

the

walls.

The undoubtedly hostile attitude of the citizens towards their new masters may have had a bearing upon his choice also.

From

the

red

sandstone

cliffs

upon

which

St. John's

was

to

stand,

the

forests

extended

unbroken

to

Delamere

and

Peckforton

and

the

tidal

waves

of

the

then-great River Dee,

unconfined

by

artificial

barriers,

broke

against

the

base

of

these

cliffs-

from

which

the

stone

for

the

new

church

was

quarried-

and

of

the

City

Walls.

The old Saxon building was swept away, a platform

cleared

and

the

church

was

laid

out

on

the

classic

plan

of Norman

cathedrals,

with

its

nave,

its

side

aisles-

terminating

in

two

low

towers-

its

central

lantern

tower,

transepts

and

choir,

round

which,

in

later

years,

were

to

spring

up

the

chauntry

chapels,

of

which

mere

ruins

remain

today.

For

a few

years

the

work

proceeded

rapidly;

the

choir

was

built,

the

great

tower

arches

were

turned

and

the

nave

arcading

erected.

Then,

in

1082,

the

good

Bishop

died

and

was

laid

to

rest

in

the

unfinished

choir

of

the

great

church

he

would

never

with

earthly

eyes

see

completed. For

a few

years

the

work

proceeded

rapidly;

the

choir

was

built,

the

great

tower

arches

were

turned

and

the

nave

arcading

erected.

Then,

in

1082,

the

good

Bishop

died

and

was

laid

to

rest

in

the

unfinished

choir

of

the

great

church

he

would

never

with

earthly

eyes

see

completed.

Peter's

successor was Robert

de

Limesey.

He was less

enthusiastic

about

the

project-

and

about

the

situation

of

Chester

in

general.

Perhaps

this

was

because

of

the

dangers

inherent

in

the

city's

location

on

the

'front

line'

of

the

Welsh

border,

or

it

may

have

been,

as

Sir

Peter

Leycester

wrote, "Robert-de-Limesie

in

order

to

possess

himself

of

the

riches

of

the

Monastery

of

Coventry,

one

of

the

richest

in

the

land,

having

been

amply

endowed

by

Earl

Leofric,

removed

his

seat

to

Coventry".

Nevertheless,

for

several

centuries

after,

the

bishops

continued

to

occasionally

style

themselves Bishop of Chester and

a palace

was

maintained

near

the

unfinished

church,

immediately

to

the

south

of

the

present

Bishop's

Palace.

After

the

move,

work

on

the

great

church

was

largely

abandoned,

the

nave

laying

open

to

the

sky

for

nearly

a century

until

around

1190,

when

later,

unknown,

hands

resumed

the

work-

and

did

not

approach

a state

of

completion

until

sometime

in

the

late

13th

century.

Nearly

four

and

a half

centuries

were

to

pass

before

the

Norman

Benedictine

Abbey

of

St.Werburgh

would

become

Chester's Cathedral instead.

Whether

some

of

the

materials

used

in

its

construction

were

inferior,

or

long

exposure

to

the

elements

had

weakened

the

structure,

but

so

it

was

that

the

Dean

and

Canons

of

what

had

by

now

become

a Collegiate

Church ("a church served by a body of canons or prebendaries; not housing the throne of a bishop and therefore not a cathedral; served by secular canons rather than monks")

became

engaged

in

a continual

struggle

to

maintain

the

building.

In

1348,

it

was

described

as

a "comely

and

sumptuous

fabric

constructed

of

stone

and

wood

of

great

breadth

and

length,

but

the

same

being

ancient

and

decayed,

repair

was

necessary

or

it

would

fall

into

irrevocable

ruin". Whether

some

of

the

materials

used

in

its

construction

were

inferior,

or

long

exposure

to

the

elements

had

weakened

the

structure,

but

so

it

was

that

the

Dean

and

Canons

of

what

had

by

now

become

a Collegiate

Church ("a church served by a body of canons or prebendaries; not housing the throne of a bishop and therefore not a cathedral; served by secular canons rather than monks")

became

engaged

in

a continual

struggle

to

maintain

the

building.

In

1348,

it

was

described

as

a "comely

and

sumptuous

fabric

constructed

of

stone

and

wood

of

great

breadth

and

length,

but

the

same

being

ancient

and

decayed,

repair

was

necessary

or

it

would

fall

into

irrevocable

ruin".

Five hundred years later, in 1860, a report on the building's condition stated, "the exterior of the church, in spite of its horrible mutilation, its decaying stone-work and barbarous modern repairs has a very remarkable, even stately, appearance, to which the grand and lofty tower, the picturesque ruins and the beautiful situation not a little contribute. The condition of the church was in every respect so bad that the inhabitants of Chester began some time ago to entertain the question of a restoration and laudable attempts were made to raise subscriptions to that purpose, but it was only within the last year that sufficient funds were obtained to justify actual operations. To effect the complete resoration of such a church would require a sum so large that the prospect of raising it may at once be considered hopeless... there is little chance of the repair of the fine tower, which is now in a very shattered and decayed state..."

Over

the

centuries,

St.

John's

had suffered

many

disasters-

the

Central

Tower

fell

down twice:

in

1468

and

1572,

to

be

followed

in

1574

by

the

collapse

of

the

West

Tower,

which

also

destroyed

four

full

bays

of

the

Norman

Nave. Then the

rebuilt

16th

century

West

Tower

fell

again, as

recently

as

Good

Friday

1881-

after

many

warnings

and

excuses

about

lack

of

money-

also

obliterating

the

Early

English

porch. The

rector, the Rev

S.

Cooper

Scott-

who

wrote

a definitive

and

lively

history

of

St. John's- described "a

rumbling

noise,

which

was

succeeded

by

a terribly

and

indescribably

drawn

out

crash,

or

rather

rattle,

as

though

a troop

of

horse

artillery

was

galloping

over

an

iron

road;

this

was

mingled

with

a clash

of

bells,

and

when

it

had

increased

to

a horrible

and

almost

unbearable

degree,

it

suddenly

ceased,

and

was

succeeded

by

perfect

stillness".

The first editor of The Cheshire Sheaf, Thomas Hughes, described the event almost immediately after it had taken place: “The night of the 14th and 15th of April, 1881, will be a melancholy one, and a memorable, in the history of the great Church of St. John's. On that night and a little after daybreak next morning, a calamity befel the church and the city, for which no amount of personal money sacrifice on the part of the citizens, or of their generous friends elsewhere, can ever adequately provide a remedy. The first editor of The Cheshire Sheaf, Thomas Hughes, described the event almost immediately after it had taken place: “The night of the 14th and 15th of April, 1881, will be a melancholy one, and a memorable, in the history of the great Church of St. John's. On that night and a little after daybreak next morning, a calamity befel the church and the city, for which no amount of personal money sacrifice on the part of the citizens, or of their generous friends elsewhere, can ever adequately provide a remedy.

The grand old Perpendicular Tower, and even more grand and graceful Early English Porch, have both in one night virtually become things of the past, for they lie today heaped together in one sad, solemn, undistinguishahle pile of ruin. Two sides only, it is true, of the steeple have as yet actually fallen; but it is almost morally certain that the two remaining ones, the southern and western faces, must one day follow the fate of the rest. Six or seven bells only, it was at first thought, out of the once melodious peal of eight, remain hanging, as it were almost literally, in mid-air: the other two, it was feared were in all probability lying shattered beneath the mass of fallen masonry- a wilderness of danger and desolation which will probably not be removable for some weeks to come.

I was sitting alone in my room, and actually reading Ormerod’s description of St. John’s, at the very instant, 10 o'clock, when the crash of masonry, mingled with the sound of tinkling bells, fell upon my ear! The conviction at once seized me that the great Tower had succumbed; for the imminence of its fall had been for some days past manifest to all who, like myself, had watched the widening cracks in the eastern and northern faces of the structure. I was on the spot in a few moments, and realized at once all my worst fears ; for there, palpable in the moonlight to every eye, ran a fearful chasm up the northern wall of the steeple; the belfry being exposed, but the bells still all, as it now turns out, standing, though awaiting as it then seemed to every one, an all but certain destiny ere a few hours should pass by! It was a sight to daze the head, and well nigh disorder the brain, of one who reverences and revels in the treasures of the past!

Exactly three centuries ago this very year, viz., in 1581, the parishioners, having their old church, with the western end in ruins, through the fall seven years previously of the eastern and southern sides of the tower, handed over to them by Queen Elizabeth, began at great cost and labour to close up again the stunted nave. Apparently also, at least two other extremities of the cruciform church were reduced and closed in at the same date, and divine service was thenceforward celebrated, on the Reformed basis, in the still handsome parish church. The steeple, too, was rebuilt as far as needful at the same period: and the work our zealous forefathers then bequeathed us has borne the wear and tear of three hundred years gallantly, till hard fate has re-enacted, now, the fearful havoc the previous fall did for the sacred fabric in 1574! Exactly three centuries ago this very year, viz., in 1581, the parishioners, having their old church, with the western end in ruins, through the fall seven years previously of the eastern and southern sides of the tower, handed over to them by Queen Elizabeth, began at great cost and labour to close up again the stunted nave. Apparently also, at least two other extremities of the cruciform church were reduced and closed in at the same date, and divine service was thenceforward celebrated, on the Reformed basis, in the still handsome parish church. The steeple, too, was rebuilt as far as needful at the same period: and the work our zealous forefathers then bequeathed us has borne the wear and tear of three hundred years gallantly, till hard fate has re-enacted, now, the fearful havoc the previous fall did for the sacred fabric in 1574!

But it has done more than this; for that one night's wreck has deprived us of the chaste and beautiful Early English Porch, which had become, as time grew on more precious and beautiful still after its nearly three centuries' accumulation of mould and decay. There it lies now, crushed and mangled beyond, it is sadly to be feared, the possibility of restoration; and thus has one more milestone, marking the city's life journey, perished before our very eyes!

The fragment remaining of the steeple, for a second fall occurred at four next morning, is probably doomed to immediate destruction. If so, old Chester will be shorn of another grand feature in its sky-line for, viewed from whatever point the city may, the massive tower of St. John's has been long a landmark familiar to the eye and dear to the sympathies of the thoughtful Cestrian, and to every intelligent visitor to our venerable city”.

25

years

before

its

fall, Hughes had

written

of

the ill-fated

West

Tower, "The

steeple

enjoys

a set

of

eight

peerless

bells,

by

far

the

most

melodious

of

their

kind

in

the

city.

Six

were

cast

in

1710

and

the

other

two

in

1734,

having

replaced

an

earlier

peal,

which

existed

here

at

least

as

early

as

the

reign

of

Henry

VII.

Doubtless,

therefore,

during

the

great

Civil

War,

when

the

news

of

a Royalist

victory

reached

the

ears

of

the

loyal

citizens,

Merrily, merrily rang the bells,

The

bells

of

St. John's

Church

tower.

And "merrily,

merrily" still

they

ring,

as

the

bridal

procession

issues

from

the

porch,

as

well

as

on

days

of

public

rejoicing-

whenever,

in

fact,

loyalty,

love

or

patriotism

need

their

witching

strains".

During

the

middle

of

the

seventeenth

century,

those

citzens

must

have

often

been

greeted

by

sounds

very

different

to

the

'merry

ringing

of

church

bells'

as

this

tower

was

used

as

a

gun

emplacement

by

Parliamentary

forces

during

the

bitter Siege

of

Chester-

an

excellent

vantage

point

from

where

they

inflicted

terrible

damage

upon

the

walls,

buildings

and

citzens

of

the

town.

(It

is

said

that

a

bullet

fired

from

here

narrowly

missed

King

Charles

I

as

he

stood

on

the

Cathedral

tower,

but

killed

the

officer

standing

next

to

him-

a

remarkable

shot!)

The

commander

of

the

Royalist

defending

forces, John,

First

Baron

Byron (an

ancestor

of

the

poet

Lord

Byron)

in

the

early

days

of

the

conflict,

among

other

precautions,

ordered

the

deliberate

destruction

of

many

buildings

lying

outside

the

walls

in

order

to

deny

cover

to

the

attackers.

The

areas

outside

the Northgate, Spital

Boughton and

the

suburb

of Handbridge,

on

the

other

side

of

the Old

Dee

Bridge were

accorded

such

drastic

treatment.

As

part

of

this

policy,

he

"left

order

for

the

pulling

down

of

St. John's

steeple,

which

(in

case

the

enemy

should

possess

the

suburbs)

would

be

very

prejudicial

to

the

city

as

overlooking

it

all,

and

from

whence

(in

the

ensuing

siege)

was

received

our

greatest

annoyance.

All

these

things

the

Mayor

promised

to

see

done,

but

performed

none

of

them". The

commander

of

the

Royalist

defending

forces, John,

First

Baron

Byron (an

ancestor

of

the

poet

Lord

Byron)

in

the

early

days

of

the

conflict,

among

other

precautions,

ordered

the

deliberate

destruction

of

many

buildings

lying

outside

the

walls

in

order

to

deny

cover

to

the

attackers.

The

areas

outside

the Northgate, Spital

Boughton and

the

suburb

of Handbridge,

on

the

other

side

of

the Old

Dee

Bridge were

accorded

such

drastic

treatment.

As

part

of

this

policy,

he

"left

order

for

the

pulling

down

of

St. John's

steeple,

which

(in

case

the

enemy

should

possess

the

suburbs)

would

be

very

prejudicial

to

the

city

as

overlooking

it

all,

and

from

whence

(in

the

ensuing

siege)

was

received

our

greatest

annoyance.

All

these

things

the

Mayor

promised

to

see

done,

but

performed

none

of

them".

Could

it

have

been

the

people's

sentimental

affection

for

the

ancient

church

that

prevented

its

destruction? Whatever

the

reason,

you

can

read Randle

Holme's melancholy

description

of

the

desolation

wrought

upon

the

city

by

the

years

of

warfare here.

The

besiegers

occupied

the

church

for

a

period

of

twenty

weeks

and

"used

it

as

a

common

place",

virtually

turning

it

into

a

fort.

The

Rev

Scott

wrote

of

the

time

when

the

parishioners

were

at

last

permitted

to

re-visit

it,

"Bitter

indeed

must

have

been

the

feelings

of

the

people

when

they

once

more

entered

within

its

sacred

walls,

and

they

must

have

regarded

with

dismay

the

desolation.What

a

cruel

sight

met

their

eyes!

The

memorials

of

the

dead

defaced

and

scattered

about

the

floors;

coats

of

arms

and

figures

on

the

tombs

used

perhaps

as

targets

for

the

soldier's

muskets;

the

pavement

broken

up,

the

windows

and

the

furniture

of

the

church

destroyed".

The

weight

of

the

Parliamentary

guns

and

the

shock

of

the

explosions

no

doubt

contributed

greatly

to

the

old

tower's

weakening.

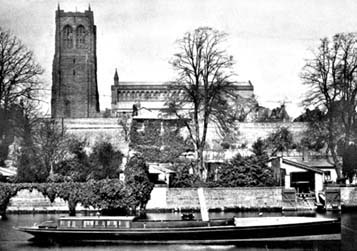

Here

is

a

beautiful

photograph

of

it

from

the River

Dee,

taken

not

long

before

its

eventual

collapse.

The

huge

tower,

standing

aloof

from

the

body

of

the

church,

was

a

familiar

sight

to

many

generations

of

Cestrians.

Notice

also

the

elegant

steam

launch

in

the

river

below. The

weight

of

the

Parliamentary

guns

and

the

shock

of

the

explosions

no

doubt

contributed

greatly

to

the

old

tower's

weakening.

Here

is

a

beautiful

photograph

of

it

from

the River

Dee,

taken

not

long

before

its

eventual

collapse.

The

huge

tower,

standing

aloof

from

the

body

of

the

church,

was

a

familiar

sight

to

many

generations

of

Cestrians.

Notice

also

the

elegant

steam

launch

in

the

river

below.

Another

fine

old

photograph

of

St. John's

tower

from

the

river

may

be

seen here-

and the remarkable

aerial

view below,

a

detail

from

John

McGahey's

famous View

of

Chester

from

a

Balloon, magnificently

portrays

the

old

church

and

its

surroundings

as

they

appeared

around

the

year

1855. (you can see more of it here).

In common with with so many places in Chester, St. John's Church is reputed to have its ghost- the cowled, silent figure of a monk which, it is said, emerges from a lost underground passage by the Dee, passes beneath the Anchorite Cell known as The Hermitage, through the ruins of the church and finishes his walk in the ruined West Tower, where he sits brooding. He is tall and his hood is pulled up, hiding his face. According to those who have heard him, he speaks in a foreign tongue. Could it, in fact, be Saxon English?

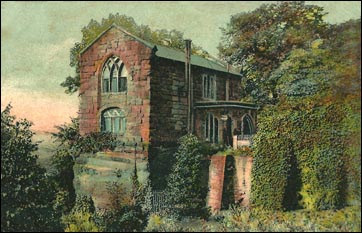

Right: this memorial in the Warburton Chapel is by a contemporary and collaborator of Sir Christopher Wren and features a standing skeleton beneath a shroud.

In the centre of this photograph may be seen a curious, ivy-clad house sitting high up on an outcrop of sandstone- all that remains of the quarry that for long existed there. It is know today as the Anchorite's Cell or the Hermitage- seen here in a charming old handcoloured postcard- and has a curious legend associated with it. It is said that King Harold Godwinson (1022-1066) didn't die at Hastings with an arrow in the eye, and it was another who was buried under the cairn of stones on the cliff edge where he was said to have fallen. Instead, he was smuggled, badly injured, to Chester by his Queen, Aldgyth, and lived out his days as an Anchorite monk in a cell in the rock. Fact or legend? It was certainly the case that Harold's Queen became a nun in Chester and when she died, she was said to have been buried in the grounds of St. John's. In the centre of this photograph may be seen a curious, ivy-clad house sitting high up on an outcrop of sandstone- all that remains of the quarry that for long existed there. It is know today as the Anchorite's Cell or the Hermitage- seen here in a charming old handcoloured postcard- and has a curious legend associated with it. It is said that King Harold Godwinson (1022-1066) didn't die at Hastings with an arrow in the eye, and it was another who was buried under the cairn of stones on the cliff edge where he was said to have fallen. Instead, he was smuggled, badly injured, to Chester by his Queen, Aldgyth, and lived out his days as an Anchorite monk in a cell in the rock. Fact or legend? It was certainly the case that Harold's Queen became a nun in Chester and when she died, she was said to have been buried in the grounds of St. John's.

As the Norman/Welsh chronicler Geraldus Cambrensis put it, "Harolde had many woundes, and lost hys left eye wyth the strooke of an arrowe, and was overcome; and escaped to the countrye of Chester, and lived holylie, as men troweth, an Anker's life, in Sayne Jame's cell, fast by Saynte John's church, and made a good end, as yt was knowen by hys last confession".

Actually, Harold had lived happily for over twenty years with Edith of the Swan Neck without actually being married to her, and they had three or four sons and two daughters together. When the king's mother and nephew were unable to do so, it was she who was reportedly brought to the battlefield to identify his body. The official story is that Harold's body was said, many years later, to have been moved from its rude grave on the Hastings clifftop and re-interred in a plain grey marble tomb at Waltham Abbey in Essex but was, tellingly, "lost for ever" when Henry VIII destroyed the building as part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries. It was only for political reasons that Harold married Aldgyth, a few months before the great events at Hastings.

The son of the Conqueror, King Henry I (1068-1135) visited the hermitage in Chester and found an ancient, one-eyed man there. Did his hood hide the disfigured features of the doomed Saxon King? We will never know- all we have today is a tale of the dark, silent figure of the monk, restlessly prowling...

The anonymous author of the early 19th century A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, recorded that "some few years ago, while altering this cell, the workmen discovered two human skeletons, deposited in coffin-shaped cavities, cut in the live rock".

The Anchorite's Cell still exists today, sitting picturesquely atop its rocky mount below St. John's, and is now a unique and attractive private residence. The Anchorite's Cell still exists today, sitting picturesquely atop its rocky mount below St. John's, and is now a unique and attractive private residence.

Before moving on to learn more about the beautiful church, I will tell you a little about an earlier bloody conflict which took place here.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the area around St. John's enjoyed a somewhat elegant seclusion from the rest of the city and a number of grand and fashionable mansions with extensive gardens were built here. Of these, three survive today- St. John's Vicarage, the former Bishop's Palace and Dee House- currently rotting away atop the unexcavated part of the Roman Amphitheatre. Several others, including St. John's House, have been demolished.

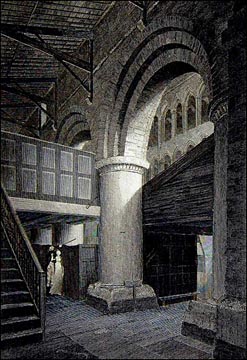

This 13th century painting- rich with detail despite its decayed condition- on one of the nave pillars was rediscovered when whitewash from Puritan days was removed in the 19th century.

Sir Hugh Cholmondeley, who owned a very large amount of property in various parts of Cheshire, had been one of the commissioners who conducted the dissolution of the collegiate church of St. John and dispersal of its property, including one of the old mansions which became known, under his ownership, as Cholmondeley House.

The family already owned a grand town house which faced what is now the Market Square and formed the centre section of the buildings between Princess Street and Hunter Street. It was here around 1608 that the Puritan Divine John Ball (1585-1640) came to serve as a tutor to the Cholmondeley children.

(This house was in the occupation of the Chamberlaine family in the early years of the 19th century and later in that century the premises were occupied by William Hewitt, a coach builder. About the year 1900 they were taken over by a similar firm and re-built. They were rebuilt once again on a grander scale in 1913 to a design by Philip Lockwood for the Westminster Coach and Motor Car Works and this remains with us today as the facade of Chester Library.

The older house of the Cholmondeleys, however, was on a site now included in the Grosvenor Park and opposite to the ruined east end of St. John's Church, being only separated from it by the path which still connects Vicar's Lane with the steps leading to the River Dee, "between Barker's Lane (the old name for Union Street) and Black Walk (by Grosvenor Park)". Some of the houses of the petty canons attached to the collegiate church and the hospital, a larger building adjoining them but more to the north, had been acquired by the Cholmondeleys and, at some date after 1605, they were probably incorporated into one grand mansion. The older house of the Cholmondeleys, however, was on a site now included in the Grosvenor Park and opposite to the ruined east end of St. John's Church, being only separated from it by the path which still connects Vicar's Lane with the steps leading to the River Dee, "between Barker's Lane (the old name for Union Street) and Black Walk (by Grosvenor Park)". Some of the houses of the petty canons attached to the collegiate church and the hospital, a larger building adjoining them but more to the north, had been acquired by the Cholmondeleys and, at some date after 1605, they were probably incorporated into one grand mansion.

During the Civil War this part of Chester suffered heavily and in a record of the devastation it was related that "the Lord Cholmondeley's house in St. John's Churchyard had been pluck'd downe and burnt by the Parliament partie as they lay in siege about Chester".

The Cholmondeleys, unlike many of the better-off families, remained in Chester during the siege and, until the suburbs were taken by the Parliamentary forces, may be assumed to have been residing in the old house.

As part of the Irish rising of 1641, a conspiracy was attempted by Lord Cholmondeley and some of his fellow Cheshire Papists. It had been ordered by Parliament that all Papists should be disarmed, but those in Cheshire refused to obey so the Trained Bands (the local militia) were employed to search for the culprits with instructions to destroy the houses of any who declined to yield.

On 20 November, the Papists, having obtained news of this intention, gathered themselves together at the Cholmondeley mansion, and in the night sallied out and commenced to batter down the walls of the city. Unsurprisingly, this made "a very great noise" and soon drew the attention of the City Watch, who were "very much amazed" but, being mostly elderly men, retreated to the city gate where they loudly cried out "treason, treason, against the city!"

By the time the Trained Bands were alerted, most of the party had escaped, but two stragglers who were captured said that the rest were running to Lord Cholmondeley's house. They were pursued and taken at the gate as the guard on duty at it had thought the fugitives belonged to the Trained Band and would not allow them to pass through to safety. By the time the Trained Bands were alerted, most of the party had escaped, but two stragglers who were captured said that the rest were running to Lord Cholmondeley's house. They were pursued and taken at the gate as the guard on duty at it had thought the fugitives belonged to the Trained Band and would not allow them to pass through to safety.

The fugitives were arrested and a strong guard left at the house so that none of the Papists there might leave. After the prisoners had been "lay'd fast" the Train Bands returned to the house and demanded admittance which was refused. Muskets were discharged at the house and when part of it had been battered down, Lord Cholmondeley escaped by a postern door which opened on to the fields.

Most of the Train Band then went into the house and searched it, and coming into a private wood-house there, to their horror came face to face with 50 Papists with charged muskets. These were discharged and 25 of them were killed. The Papists retreated through a back door out of the wood-house but were met by the remainder of the Trained Band and a battle ensued. At length the Papists were routed and "trusted to the swiftness of their feet", but 19 of them, including their leader, Henry Starkey, were nontheless shot in the back. These unfortunates were later "buried in the highway together".

An archaeological investigation of the area in 2007 recovered, among much else, a number of musket balls that were probably used during this conflict.

How he got away with such mischief is unknown, but, by 1645 Lord Cholmondeley, whose household numbered 22, was back comfortably residing in the Northgate Street house mentioned earlier to which he had retired when the one in St. John's Churchyard had been brought to ruin. Curiously, rumours of its total destruction seem to have been exaggerated as it was mentioned a century later on De Lavaux's map of 1745 and also on several other maps of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

We see the old mansion still standing proud, albeit in deep shadow, a further century on, in 1855 at the bottom of the above detail from John McGahey's remarkable aerial view of Chester, where it looks to be in excellent condition. A mere twelve years after the view was published, the last traces of the once-grand buildings had vanished and Grosvenor Park was formed and presented to the City of Chester by the Marquess of Westminster in 1867.

Now

go

on

to part

II of

our

exploration

of St. John's

Church or view some of the pictures in our new gallery... |