s

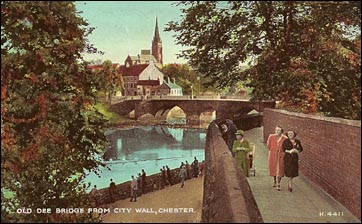

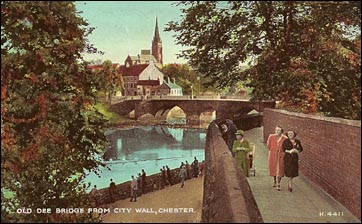

we approach the end of the Groves our hearing

is filled with the roar of water rushing over the weir and the scene is dominated

by a magnificent sandstone bridge crossing the river. This is the venerable Old

Dee Bridge, comprising seven unequal arches and built, much as we see it

today, about the year 1387 on the site of a succession of earlier wooden bridges

and a pre-Roman fording place. s

we approach the end of the Groves our hearing

is filled with the roar of water rushing over the weir and the scene is dominated

by a magnificent sandstone bridge crossing the river. This is the venerable Old

Dee Bridge, comprising seven unequal arches and built, much as we see it

today, about the year 1387 on the site of a succession of earlier wooden bridges

and a pre-Roman fording place.

The bridge is mentioned as part of Chester's entry in the Domesday

Book: "When, for the purpose of repairing or rebuilding the wall or the bridge of

the city, the proper officers commanded that one man be furnished from each

hide, the lord of such man that did not attend was fined fourty shillings to

the King and the Earl".

Successive bridges were washed away by flood tides in 1227, 1280, 1297 and 1353.

The later stone structure seems to have been more resistant to inundations:

on 16th January 1551, "There arose in the night a mighty great wind and the

flood came to such a height that many trees were left by the ebb, on the top

of Dee Bridge".

Thomas Pennant (1726-98), Flintshire landowner, naturalist and travel writer wrote of it in 1773, "The approach to the city is over a very narrow and dangerous bridge, of seven irregular arches, till of late rendered more inconvenient by the antient gateways at each end, formerly necessary enough, to provent the inroads of my countrymen, who often carried fire and sword to these suburbs; which were so frequently burnt, as to be called by the Britons Tre-boeth, or the burnt town"...

An older document records how, in the 13th century, Llewellyn, Prince of Wales "gathered a mighty band and with it inflicted much harm even unto the gates of the city of Chester. The city had often been affrighted with the like scare-fires and was lastly defended with a wall made of the Welsh-men's heads on the south side of Dee in Handbridge."

Handbridge

was

burned

once

again,

but

this

time

by

the

citizens,

during

the

Siege

of

Chester

in

1645

to

prevent

Parliamentary

forces

taking

cover

there."Handbridge

has

once

again

become

Treboeth,

being

burnt

by

the

command

of

the

Governor

Lord

Byron

to

prevent

their

nesting

others"

wrote

one

of

the

besieged

in

his

diary. Handbridge

was

burned

once

again,

but

this

time

by

the

citizens,

during

the

Siege

of

Chester

in

1645

to

prevent

Parliamentary

forces

taking

cover

there."Handbridge

has

once

again

become

Treboeth,

being

burnt

by

the

command

of

the

Governor

Lord

Byron

to

prevent

their

nesting

others"

wrote

one

of

the

besieged

in

his

diary.

During

this

period,

both

sides

made

desperate

sorties

over

the

old

bridge

and

almost

incessant

fighting

occured

in

the

area,

a situation

difficult

to

imagine

as

we

gaze

upon

the

bustling,

but

peaceful

scene

today.

Despite the bridge being so vital to their prosperity, the citizens were often reluctant to assume responsibility for its repair, and in 1387 Richard II was persuaded to grant them sums of money for this purpose. Letters Patent granted to the citizens on 25 July 1387 state: "Know ye that of our special grace and at the supplication of our lieges, the Commonalty of our town of Chester, and for consideration that as many have been drowned in the water of the Dee since the bridge has been destroyed and broken. And also, because the same town for that reason is very greatly impoverished as we are informed, we have granted to the fabric and repair of the aforesaid bridge all the profits of the Passage of the said water at Chester and the Murage which used to be granted there for the walls, to be received until that bridge is rightly and reasonably completed".

Twenty years later, Letters Patent granted by Henry Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester, refer to "the completion and finishing of the Tower on the Dee Bridge begun in the time of Richard, late King of England".

The anonymous author of A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, published in the first years of the nineteenth century, wrote about the Old Dee Bridge, "The bridge is built upon seven arches; the passage over it is very disagreeable, and indeed when crowded, rather dangerous, owing to its being so narrow; a new bridge would certainly add much to the convenience of the public and the appearance of the City". The anonymous author of A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, published in the first years of the nineteenth century, wrote about the Old Dee Bridge, "The bridge is built upon seven arches; the passage over it is very disagreeable, and indeed when crowded, rather dangerous, owing to its being so narrow; a new bridge would certainly add much to the convenience of the public and the appearance of the City".

The author's desired benefits of convenience and appearance actually came about thirty years later with the opening of the magnificent Grosvenor Bridge.

Left: a salmon fisherman attends to his nets before the Old Dee Bridge in this photograph by the famous Liverpool photographer Edward Chambré Hardman. See more of his splendid images of Chester and Liverpool here.

At

the

far

end

of

the

bridge

is

an

attractive

green

area

bordered

by

a mixture

of

19th

century

cottages

and the exceedingly ugly Salmon Leap apartment

blocks.

That their occupants enjoy some of the most magnificent views in the city is undisputed, but that

such

eyesores

could

have

been

allowed

in

such

a sensitive

location in the first place

has

long

been

a source

of

wonder

to

everyone else.

Soon

after

they

were

built,

in

1972,

the authors of the Chester

Riverside

Study commented dryly,"The

new

riverside

flats

at

Mill

Street

are

generally

regarded

as

an

unfortunate

design

for

this

location". Which

is

putting

it

mildly.

Their site was formerly occupied by industrial premises such as the factory of Messrs T. Nicholls, manufacturers of tobacco and snuff, which was established here in the 1780s. Those buildings were entirely demolished in the 1960s- our photograph shows them just before this event- the flats were built at the Old Dee Bridge end of the site and the rest was landscaped and a footpath to the Meadows constructed. At the far end, the Salmon Leap survives and the waterwheel which once powered Nicholl's snuff mill has been restored. A small generating station now stands where a smaller tobacco works and a tallow candle works used to be on Cherry Tree Island at the end of the weir.

Standing close to the

Handbridge end of the bridge is The Ship Inn, whose licence can be traced back to 1770 when the licencee was Mr Stephen Hyde. During the period 1850-60, the licencee, Mr William Dutton, was a man of many talents, for as well as landlord he was also a practicing blacksmith, farrier and wheelwright. The Ship was indeed a waterside hostelry with around it, manufacturers of twine and rope for fishing nets. Fisher folk thronged the courts around Greenaway Street in old-time Handbridge, and they had the run of the river. They

all

had

their

own

jealously-guarded

named

spots

to

fish from,

such

as Marshead, Lane

End, Under

the

Hills, Crane and Littlewood. Standing close to the

Handbridge end of the bridge is The Ship Inn, whose licence can be traced back to 1770 when the licencee was Mr Stephen Hyde. During the period 1850-60, the licencee, Mr William Dutton, was a man of many talents, for as well as landlord he was also a practicing blacksmith, farrier and wheelwright. The Ship was indeed a waterside hostelry with around it, manufacturers of twine and rope for fishing nets. Fisher folk thronged the courts around Greenaway Street in old-time Handbridge, and they had the run of the river. They

all

had

their

own

jealously-guarded

named

spots

to

fish from,

such

as Marshead, Lane

End, Under

the

Hills, Crane and Littlewood.

Guide and author Joseph

Hemingway,

wrote

in

1835, "In

that

useful

article,

salmon,

no

market

in

the

kingdom

did,

some

few

years

ago,

excel

it;

indeed,

such

was

the

profusion

of

that

valuable

fish,

that

masters

were

often

restricted,

by

a

clause

in

the

indentiture,

from

giving

it

more

than twice

a

week to

their

apprentices.

Though

the

bounty

of

providence,

in

this

particular,

is

yet

unabated,

such

restriction

is

no

longer

necessary-

some

artificial

cause,

or

other

very

kindly,

rendering

this

fish,

at

the

present

day,

a

delicacy

even

to

the

masters

themselves...

The

supply

was

so

great,

that

after

furnishing

our

own

market

for

the

city

and

neighbourhood,

five

or

six

carts

were

employed

in

conveying

it

for

sale

to

distant

places".

Due to the increasing quantity of fish being taken from the river, by 1880, it was deemed necessary to introduce restrictions and Fishery Boards became responsible for licensing the fishermen. But at £5 a licence this proved a considerable financial burden so the Rector of the parish, Rev Henry Grantham, formed a Fishermen's Association for the encouragement of the salmon fishermen, with a penny bank to enable them to save for their licence. Each year he gave a ton of coal to the fisherman who caught the first Dee salmon. This later became a guinea paid by the Rector of Handbridge to the fisherman who brings the first salmon for him to see. Contrary to popular belief, the Rector does not receive the first salmon.

The Handbridge fishermen still ply their craft, and their fishing boats and nets can be seen below the bridge when the men are not out on the water. Nowadays, however, fishing does not bring in sufficient livelihood, and the majority of the fishermen also have other employment. Nor do they now live as once they did in Greenway Street- their simple cottages have given way to more modern dwellings but this old thoroughfare which rises uphill from the river retains its cobbles to this day.

Until it was removed in 1850, a maypole once stood at the Handbridge end of the Old Dee Bridge. The American author, Washington Irving (best remembered today for his stories The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, in which the schoolmaster Ichabold Crane meets with a headless horseman, and Rip Van Winkle, about a man who falls asleep for 20 years)- recalled seeing it on a visit to Chester around 1825, "I shall never forget the delight I felt on first seeing a May-pole. It was on the banks of the Dee, close by the picturesque old bridge that stretches across the river from the quaint little city of Chester. I had already been carried back into former days by the antiquities of that venerable place... the May-pole on the margin of that poetic stream completed the illusion. My fancy adorned it with wreaths of flowers and peopled the green bank with all the dancing revelry of May-day. The mere sight of this May-pole gave a glow to my feelings and spread a charm over the country for the rest of the day". Until it was removed in 1850, a maypole once stood at the Handbridge end of the Old Dee Bridge. The American author, Washington Irving (best remembered today for his stories The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, in which the schoolmaster Ichabold Crane meets with a headless horseman, and Rip Van Winkle, about a man who falls asleep for 20 years)- recalled seeing it on a visit to Chester around 1825, "I shall never forget the delight I felt on first seeing a May-pole. It was on the banks of the Dee, close by the picturesque old bridge that stretches across the river from the quaint little city of Chester. I had already been carried back into former days by the antiquities of that venerable place... the May-pole on the margin of that poetic stream completed the illusion. My fancy adorned it with wreaths of flowers and peopled the green bank with all the dancing revelry of May-day. The mere sight of this May-pole gave a glow to my feelings and spread a charm over the country for the rest of the day".

A

footpath

here

will

take

you

back

to Queen's

Park

Bridge and

the Meadows,

or,

if

you

carefully

cross

the

busy

road,

next

to

the Ship you

will

see

the

entrance

to

a tree-lined

open

green

area.

Today

this

serves

as

a public

park

and

it

has

for

centuries

been

known

as Edgar's

Field,

being

the

legendary

site

of

the

10th

century

Royal

Palace

of

King

Edgar 'The Peacemaker'.

(Read the splendid old legend of how he was rowed on the River Dee to St. John's Church by six lesser kings here). Earlier

still,

there

was

a large

quarry

here

which

was

the

source

of

much

of

the

stone

used

in

the

construction

of

the

Roman

fortress.

This

was

a superior

material

to

that

used

by

some

later

generations

of

builders,

as

we

saw

when

we

visited

the Cathedral and

the Northgate. Excavations

have

shown

that

work

in

the

quarry

ceased

around

the

end

of

the

fourth

century

AD.

On

the

eastern

face

of

a remaining

sandstone

outcrop

may be seen a remarkable survivor-

a carved

Roman representation

of

the

goddess Minerva,

the

patron

of

all

rivers

and

springs

in

Britannia,

and

also

protector

of

of

soldiers

and

craftsmen.

Situated

as

she

is

here,

facing

the

bridge

and

the

ancient

route

to

the

south,

she

was

revered

as

the

protector

of

travellers.

Hemingway

calls

her

the Diva

Armigera

Pallas. Also

known

as Pallas and Athena,

she

was

one

of

the

most

popular

deities

and

was

worshipped

at

the five-day

March

festival

of Quinquatrix. On

the

eastern

face

of

a remaining

sandstone

outcrop

may be seen a remarkable survivor-

a carved

Roman representation

of

the

goddess Minerva,

the

patron

of

all

rivers

and

springs

in

Britannia,

and

also

protector

of

of

soldiers

and

craftsmen.

Situated

as

she

is

here,

facing

the

bridge

and

the

ancient

route

to

the

south,

she

was

revered

as

the

protector

of

travellers.

Hemingway

calls

her

the Diva

Armigera

Pallas. Also

known

as Pallas and Athena,

she

was

one

of

the

most

popular

deities

and

was

worshipped

at

the five-day

March

festival

of Quinquatrix.

Later

generations,

taking

her

for

the

Virgin

Mary,

also

worshipped

and

protected

her,

and

she

remains

with us to

this

day-

albeit

a severely

weathered

shadow

of

her

original

self-

and

claimed

to

be

the

only

representation

of

a Classical

goddess

still

in

its

original

position

anywhere

in

Western

Europe.

To quote again from A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, its author wrote in the opening years of the nineteenth century, "Over the bridge in the front of a rock in the field on the right is cut a rude figure of the Dea armigera, Minerva, with her bird and altar. Here were formerly some ancient buildings, whose scite is marked by certain hollows; for the ground, probably over the vaults, gave way and fell in, within the remembrance of persons now alive. Tradition calls the spot the scite of the place of Edgar, from whence he was rowed in the year 973 by eight tributary kings to the monastery of St. John Baptist, and back again to his palace."

Our photograph shows the shrine as it now is- a shocking mess. A fine information board was some time ago provided by the City Council, explaing the history of the shrine and included a reconstruction of the statue as it may once have appeared, finely detailed and painted in bright colours. This has now disappeared- doubtlessly due to the attentions of vandals- and only the metal poles that once supported it remain.

That said, during the Summer of 2010, with the assistance of The Friends of Edgars Field, a radical programme of improvements were undertaken, including repairs to the shrine, attractive and imaginative new equpment in the play area, tree maintainance and much more. The Friends are a group of local people who are dedicated to improving, publicising- and defending from development, as you'll see when you visit their fascinating and informative website- this unique and historic open space next to the River Dee in Handbridge.

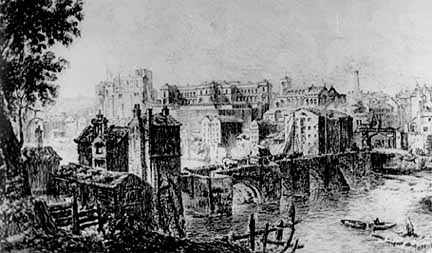

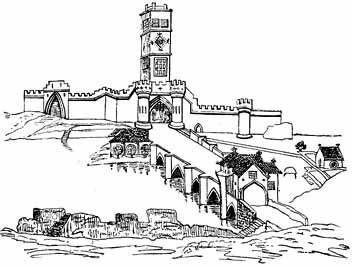

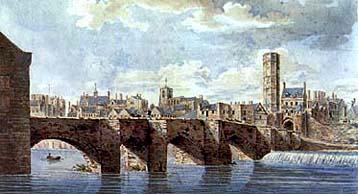

The

Old

Dee

Bridge

was

reconstructed

in

stone

in

1387, complete

with

strong

towers

and

a drawbridge,

and

the

Handbridge

end

was

rebuilt

again

in

1499

when

defences

were

added

to

give

it

greater

protection.

It

was

necessary

to

repair

the

bridge

once more after

its

battering

during

the

Civil

War

(when the tall tower seen in our illustration, known as Tyrer's Tower, was also destroyed) and

in

1826

it

was

widened,

its

narrowness

having

longbeen

a serious

obstruction

to

traffic

in

the

growing

town.

This

involved

the

corbelling

out

of

the

footwalk

on

the

east

side

and

the

building

of

new

arches

in

front

of

the

east

side

of

the

first

and

third

arches

and

the

west

side

of

the

seventh,

but

the

14th

century

moulded

arch

openings

remain

visible.

The

seaward

side-

seen

at

the

top

of

the

page

in

the

photograph

of

a salmon

fisherman

by Edward

Chambré Hardman-

remains

substantially

as

it

was

600

years

ago. The

Old

Dee

Bridge

was

reconstructed

in

stone

in

1387, complete

with

strong

towers

and

a drawbridge,

and

the

Handbridge

end

was

rebuilt

again

in

1499

when

defences

were

added

to

give

it

greater

protection.

It

was

necessary

to

repair

the

bridge

once more after

its

battering

during

the

Civil

War

(when the tall tower seen in our illustration, known as Tyrer's Tower, was also destroyed) and

in

1826

it

was

widened,

its

narrowness

having

longbeen

a serious

obstruction

to

traffic

in

the

growing

town.

This

involved

the

corbelling

out

of

the

footwalk

on

the

east

side

and

the

building

of

new

arches

in

front

of

the

east

side

of

the

first

and

third

arches

and

the

west

side

of

the

seventh,

but

the

14th

century

moulded

arch

openings

remain

visible.

The

seaward

side-

seen

at

the

top

of

the

page

in

the

photograph

of

a salmon

fisherman

by Edward

Chambré Hardman-

remains

substantially

as

it

was

600

years

ago.

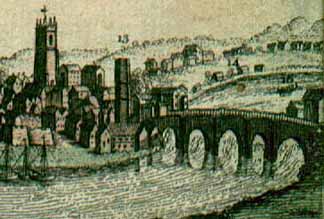

We see it again in a small detail from a view of Chester (above) which was published in the London Magazine in 1753 and, more clearly, in this interesting sketch by historian Randle

Holme

III (1627-1699).

Just

a year

after

the

widening

of

the

Old

Dee

Bridge

in

1826,

the

foundation

stone

of

a second

river

crossing,

the

new Grosvenor

Bridge was

laid

by

the

Marquis

of

Westminster.

Today, the picturesque bridge stands devoid of towers, drawbridge and portcullis,

but remains a busy bottleneck throughout the day as- despite its 19th century

widening- it is still too narrow for two-way traffic, the flow being controlled

by traffic lights.

In the Spring of 1999 the carriageway was resurfaced and laid out to include

an advanced stop line for the benefit of cyclists. At

the same time a series of safety checks were made, which found that, after over

six hundred years of constant use, the ancient structure was coping very well

with modern traffic. These investigations also found evidence of a cobbled road

surface below the level of the present carriageway.

Millers

of

Dee

You

can

hardly

failed

to

have

noticed

the

great

weir

in

front

of

the

Old

Dee

Bridge.

As

far

as

we

know,

this

was

constructed

around

the

year

1093

on

the

orders

of Hugh

Lupus,

first

Earl

of

Chester,

to

supply

power

to

his

corn

mills

which

were

situated

where

you

see

the

small

modern

generating

station

at

the

north

end

of

the

bridge.

It is the oldest surviving structure of its kind in Britain.

In

earlier

times,

the

river

seems

not

to

have

been

navigable

all

year

round,

for

the

Romans

had

to

haul

the

bricks

and

tiles

produced

at

their

industrial

centre

at Holt overland

from

Heronbridge

some

of

the

time.

This

was

later

to

change: "The

river

of

Dee

was

drawn

unto

the

said

cittie

with

great

charge

by

the

said

Earle or

some

of

his

predecessors

before

the

Conquest,

from

the

anciente

course

it

held

before,

a

myle

or

two

distant

from

the

cittie,

and

a

passage

cut

out

of

the

rock

under

the

walls

of

the

said

cittie". In

earlier

times,

the

river

seems

not

to

have

been

navigable

all

year

round,

for

the

Romans

had

to

haul

the

bricks

and

tiles

produced

at

their

industrial

centre

at Holt overland

from

Heronbridge

some

of

the

time.

This

was

later

to

change: "The

river

of

Dee

was

drawn

unto

the

said

cittie

with

great

charge

by

the

said

Earle or

some

of

his

predecessors

before

the

Conquest,

from

the

anciente

course

it

held

before,

a

myle

or

two

distant

from

the

cittie,

and

a

passage

cut

out

of

the

rock

under

the

walls

of

the

said

cittie".

Apart from improving the navigation, this produced a fast-flowing deep watercourse ideal for supplying power to watermills, whose construction, together with the strengthening of the Castle and city walls, were one of the first acts of Chester's new Norman masters. Hugh also reserved the Earl's Pool (later the King's Pool ), next to the causeway, for his private fishing interests and granted the Abbot of St.Werburgh's Abbey tithes for a mill "this side of the bridge" and fishing rights. He also granted three score fisheries, known as stalls, above the weir to several of his dependants.

Under the Earls of Chester, the mills on the Dee constituted the manorial mills of the city (Northgate Street excepted) and the custom of Soke Rights was established, which compelled the citzens (excepting the occupants of the Abbey and other religious houses) to take their corn to the Earl's mills to be ground- a lucrative monopoly which realised a handsome profit, the mills being constantly busy. The millers who worked here would raise their fees from the common people by taking a quantity of grain from each sack, but were often accused of taking more than their legal due and violent disagreements were common, often involving the use of lethal weapons. For centuries after, to call someone a 'Miller of Dee' was considered a serious insult, implying as it did dishonest trading practices.

There was a jolly miller once,

lived on the River Dee,

He worked and sang from morn till night,

no lark more blithe than he

And this the burden of his song

For ever used to be-

"I care for nobody, no, not I,

If nobody cares for me" |

In

1237,

the

Crown

took

over

the

Earldom

of

Chester,

and

the

Dee

Mills

became

the King's

Mills,

becoming

extensive

and

increasingly

lucrative,

especially

when

sub-let,

as

for

example

in

1277,

when

the

master

mason Richard

the

Engineer, who

worked

upon

the Cathedral and Conwy

Castle,

obtained

a

12

year

lease

from

the

King

for

a

monopoly

on

the

Mills

and

fishery

of

the

Dee

for

the

huge

sum

of £200

per

year.

Richard

may

not

have

found

this

as

good

a

bargain

as

he

may

have

wished:

several

times

during

the

1280s,

the

mills,

weir

and

salmon

cages

suffered

severe

flood

damage-

at

one

time

putting

the

former

out

of

action

for

three

months.

By

1600,

when

Alderman Edmund

Gamull purchased

the

mills,

there

were

at

least

eleven

water

wheels

operating:

six

for

grinding

corn,

two

for

raising

water

to

the

Bridgegate

Tower

and

three

for

fulling

cloth-

that

is,

for

beating

new

cloth

to

cleanse

and

thicken

it.

If

you

would

like

to

know

more

about

how

these

operations

were

carried

out, George

Skene's description of

the

workings

of

the

mills,

written

in

1729,

makes

fascinating

reading.

"If thou hadst the rent of Dee Mills thou would'st spend it". Cheshire proverb concerning extravagence: 15th century

The weir was the source of many problems, notably that it made made navigation of the full length of the river impossible and that it caused flooding to the lands upstream. It was thus the subject of numerious legal disputes. In 1608, for example, it was decreed that "one full third of the said Weyre be pulled down and the river there made open", but the interests of the wealthy mill owners would have suffered by this and the order was not carried out. Welsh landowners at the time were particularly incenced at this and threatened to march on Chester to do the job themselves. The weir was the source of many problems, notably that it made made navigation of the full length of the river impossible and that it caused flooding to the lands upstream. It was thus the subject of numerious legal disputes. In 1608, for example, it was decreed that "one full third of the said Weyre be pulled down and the river there made open", but the interests of the wealthy mill owners would have suffered by this and the order was not carried out. Welsh landowners at the time were particularly incenced at this and threatened to march on Chester to do the job themselves.

Just

after

the

end

of

the

Civil

War,

the

city

authorities,

concerned

with

the

declining

state

of

the

river,

ordered

that

the

weir

and

mills

should

be

demolished,

so

that

the

water

could

flow

rapidly

out

to

the

estuary,

sweeping

with

it

the

silt

that

was

continually

clogging

up

the

Dee's

channels. The following petition, dated April 1647, the first year after the city had been taken by the Parliament, was addressed to the House of Lords, and is preserved among its records:

"Petition of the Aldermen, Merchants, and Citizens of the City of Chester. The River Dee is choked up and made unnavigable by reason of the stone causey erected near the city, to serve the Dee Mills, which for many years has occasioned a great decay of trading, and frequent inundations on the Welsh side. The Commissioners of Sewers for these parts during King James's reign resolved that the causey should be demolished, but this resolution took no effect in regard of the power of those whose private interest in the mills was concerned. Petitioners pray that they might have an ordinance for taking down tne causey and mills, and that the materials may be used for erecting tide mills for the service of the city."

Like

so

many

local

authority

decisions-

down

to

the

present

day-

that

clash

with

private

interests,

no action was taken. Silting

continued apace

and

the

Dee

continued

to

be

the

source

of

much

local

anxiety. As late as the 1890s,

proposals were made to raise the height of the weir to prevent high tides from reaching the upper river- and even to build a second weir downstream- but, once again, nothing was done.

In

April

1895,

the

Dee

Mills,

seen

in

their

final

form

in

the

old

photograph

above,

were

purchased

by

the

Corporation,

only

to

sustain

serious

damage

a

month

later

in

the

last

of

a

long

series

of

fires,

after

which

they

were

closed. There

was

a

brief

revival

in

1902,

when

Messrs.

Rigby

of

Frodsham

Mill

temporarily

resumed

production

in

the

workable

remaining

portion

of

the

mill.

As

an

experiment

in

the

commercial

use

of

the

river,

they

carried

a

cargo

of

wheat

in

a

Swedish

ship,

which

was

piloted

to

the

Mill

Wharf

and

successfully

discharged.

The

experiment

was

not

repeated,

however,

as

the

berth

against

the

mill

did

not

give

sufficient

depth

of

water

for

the

vessel,

which

had

to

be

moved

to

mid-channel

for

several

hours,

resulting

in

a

loss

of

valuable

time

between

the

tidal

high

waters.

Soon

after,

the

Dee

Mills

closed

for

good

and

demolished

after

more

than

8

centuries

of

continuous

service. Swedish

ship,

which

was

piloted

to

the

Mill

Wharf

and

successfully

discharged.

The

experiment

was

not

repeated,

however,

as

the

berth

against

the

mill

did

not

give

sufficient

depth

of

water

for

the

vessel,

which

had

to

be

moved

to

mid-channel

for

several

hours,

resulting

in

a

loss

of

valuable

time

between

the

tidal

high

waters.

Soon

after,

the

Dee

Mills

closed

for

good

and

demolished

after

more

than

8

centuries

of

continuous

service.

Left: the tranquil sight of the Old Dee Bridge and fishing craft viewed from upriver in late January 2008. Photograph by the author.

Above

is

a

fine

watercolour

by

the

matchless Moses

Griffith (1747-1819)

showing

the

bridge

before

it

was

widened.

The

Bridgegate

may

be

seen,

surmounted

by

a

tall

octagonal

water

tower-

of

which

more

later.

To

the

left

is

the

ancient

church

of St. Mary-on-the-Hill,

and

left

again

may

just

be

seen

the

cupola

of

the Shire

Hall,

sadly

demolished

along

with

the

rest

of

the

medieval Castle at

the

end

of

the

18th

century.

Chester's

original

power

station

was

built

in New

Crane

Street in

1895. It

still

stands- or at least part of its facade does-

having

been

saved

thanks

to

a

two-year

campaign

of

public

opposition to a proposal to demolish it.

By 1911, a

dramatic

increase

in

demand

for electricity meant that the old steam-powered station had reached its maximum load so, in the same year, the City Electrical Engineer, S E Britton proposed a scheme for the construction of a hydro-electric station to be erected on the site of the recently-removed Dee Mills. His plans were criticised by the Chester & North Wales Architecural Society, who declared that the proposed building was out of harmony with the Old Dee Bridge.

The society offered their advice, suggesting that the building should be in a style more in keeping with that of the bridge and this was accepted. When the station was

opened

in

1913, it was the only hydroelectric plant in Britain that could handle both tidal and headwaters and the design was taken up in York in 1923. It ceased generating electricity in

1950,

but soon after extraction

of

water

from

the

Dee

was

authorised,

and

the

station

was

taken

over

by

the

West

Cheshire

Water

Board,

who

leased

it

to

the

council

in

1958,

from

when

the

former

hydro-electric

power

station

was

used

as

a

water

pumping

facility,

a

practice

which

continues

to

this

day.

Now go on to part II of

our story of the Bridgegate...

Curiosities from Chester's History no. 17 Curiosities from Chester's History no. 17

- 1602 The Bubonic Plague broke out in St. John's Lane; 60 a week died;

no fairs held. Plague cabins were erected for the infected between the Watertower and the river.

- 1603 Queen Elizabeth I died and was succeeded by her cousin James VI of

Scotland, who became James I (1566-1625) of England. The High Cross was re-guilded.

Eight hundred and twelve persons died of the plague in Chester. Tudor House

in Lower Bridge street built (despite it saying 1503 above the door!)

- 1605 Thirteen hundred and thirteen out of a population of about seven thousand died of the plague in Chester; County Courts held

at Tarvin on account of it. Romney attributed a major cause of the pestilential

visitations to the "stagnant filthyness of streets, accumulated filth, neglected

public dunghills and open drains, due to the unpaved streets... (for example)

the puddle which had formed at the Eastgate which became so deep as to require the Mayor's orders to remove it".

- 1604 The most ancient of the Cathedral bells, inscribed "I sweetly tolling, men do call, to taste the meat that

feeds the soul"- dates from this year.

- 1605 The Plague very violent this year. It is said that not a house in the city was spared except

one in Watergate Street, which still stands (although rebuilt in 1862)-

and known as 'God's Providence House'. On its front it carries a beam from

the original building inscribed "God's Providence is Mine Inheritance". The Gunpowder Plot: Guy Fawkes arrested in cellars of Parliament and accused

of trying to blow up House of Lords during James I's state opening of Parliament.

- 1607 Great exertions made to have the Dee causeway removed (see above)

in order to prevent the overflow of the meadows, and that the river being

scoured, ships might pass again close to the city.

- 1608 Another Plague in the city. Extensive repairs carried out to the

City Walls between the Watergate and

the Watertower, apparently to a poor

standard, for within a year, they had again fallen into disrepair.

- 1613 Entry in city expenses: "Paid to Stammering Davye for clearing the

watercourse at Newgate, vi d." The plaque above the doorway of the Phoenix

Tower, carved by Randle Holme III, commemorating its use by the

Painters, Glaziers, Embroiderers and Stationers was put in place this year.

- 1614 Pocohontas, American Indian princess, marries

John Rolfe

- 1615 Moreton, Bishop of Chester died. "He was a great scolar and writer

against the Papists, but no great housekeeper, and therefore did not obtain

the love of the clergy..."

- 1616 Prince Charles (soon to be the ill-fated King Charles I) invested

as Earl of Chester

- 1619 William, Earl of Derby, had a Cockpit erected under the Cty Walls near St. John's Church. First Negro slaves in N. America arrive in Virginia

- 1620 The Pilgrim Fathers sail from Plymouth in

the Mayflower. Oliver Cromwell is denounced because he participates in the "disreputable game of cricket"

|

s

we approach the end of the Groves our hearing

is filled with the roar of water rushing over the weir and the scene is dominated

by a magnificent sandstone bridge crossing the river. This is the venerable Old

Dee Bridge, comprising seven unequal arches and built, much as we see it

today, about the year 1387 on the site of a succession of earlier wooden bridges

and a pre-Roman fording place.

s

we approach the end of the Groves our hearing

is filled with the roar of water rushing over the weir and the scene is dominated

by a magnificent sandstone bridge crossing the river. This is the venerable Old

Dee Bridge, comprising seven unequal arches and built, much as we see it

today, about the year 1387 on the site of a succession of earlier wooden bridges

and a pre-Roman fording place.