ontinuing

our

stroll

along

City

Walls

Road,

we

soon

come

to

the

distinctive

buildings

of

the former Chester

Royal

Infirmary. ontinuing

our

stroll

along

City

Walls

Road,

we

soon

come

to

the

distinctive

buildings

of

the former Chester

Royal

Infirmary.

The

hospital

finally

closed

in

1993

after

230

years

of

medical

care

on

the

site,

services

were

transferred

to

the Countess

of

Chester

Hospital on

Liverpool

Road

and

the

site

was

sold

for

new

housing. The City Walls Medical Centre remains, however, situated

just behind the old Infirmary on St. Martin's Way.

The

Infirmary

was

founded

as

a

charitable

institution

in

1755

when

it

was

housed

in

the

upper

part

of

the Bluecoat

School,

outside

the Northgate and

the

first

patient

was

one

William

Thompson

of

St.

Mary's

Parish,

who

was

admitted

with

a

wounded

hand

on

November

11th,

1755. Among

Chester's

archives

are

a

complete

record

of

the

names

and

ailments-

including

asthma,

consumption,

jaundice,

dropsy,

scrofula,

scurvy,

worms

and leprosy-

of

every

patient

treated

here,

amongst

which

were

several

cases

of

women

treated

for hysterics.

The

Bluecoat

soon

became

hopelessly

overcrowded,

and so,

in

1761

a

purpose-built

hospital,

designed

to

accomodate

100

patients,

was

erected

upon

open

ground

within

the

city

walls,

a

location

known

as St. Martin

in

the

Fields-

also,

until

the

coming

of

the Inner

Ring

Road,

the

name

of

the

old

road

which

ran

along

the

farther

side

of

the

site.

You

can

still

see

the

date

inscribed

above

the

main

door.

The

original

medical

staff

comprised

three

physicians

and

three

surgeons.

A

board

of

governors

was

responsible

for

the

admission

and

discharge

of

patients,

and

they

were

also

responsible

for

administration.

The

medical

staff

themselves

also

served

as

governors. The

original

medical

staff

comprised

three

physicians

and

three

surgeons.

A

board

of

governors

was

responsible

for

the

admission

and

discharge

of

patients,

and

they

were

also

responsible

for

administration.

The

medical

staff

themselves

also

served

as

governors.

To

be

admitted

a

patient

had

to

have

a

letter

from

a

subscriber:

a

two

guineas

per

year

subscriber

was

entitled

to

recommend

one

in-patient

and

two

out-patients.

Frequent,

and

often

justified,

may

be

modern

complaints

about

health

service

funding,

but,

in

the

middle

of

the

eighteenth

century,

no

public

money at

all was

provided

for

medical

and

other

social

services

(and

would

not

be

for

the

best

part

of

the

next

two

centuries).

It

was

all

left

to

the

charity

and

benevolence

of

the

well-to-do

and

the

Infirmary

itself

was

supported

entirely by

subscriptions

and

donations, and

there

were

occasions

when

it

was

actually

threatened

with

closure

due

to

lack

of

money. When,

in

September

1780,

the

Infirmary

published

its

accounts,

it

became

clear

that

the

sums

contributed

were

woefully

inadequate

to

maintain

the

standard

of

service

to which they

aspired.

In

Chester itself,

167

subscribers

annually

contributed £288 17s

and

in

the

countryside

43

contributed

£15 4s.

In

North

Wales,

28

people

gave

£73

and

four

subscribers

from

other

surrounding

areas

gave twelve

guineas (£12 12s). In

Chester itself,

167

subscribers

annually

contributed £288 17s

and

in

the

countryside

43

contributed

£15 4s.

In

North

Wales,

28

people

gave

£73

and

four

subscribers

from

other

surrounding

areas

gave twelve

guineas (£12 12s).

Interestingly,

in

the

same

year,

Thomas

Grosvenor

and

William

Bootle

were

re-elected

without

contest

as

Chester's

Members of Parliament

after

regaling

all

comers

with

extravagant

'entertainment'

at

the

principal

inns.

The

money

so

lavished

on political ambition would

doubtlessly have

proved

a

godsend

to

the

cash-strapped

Infirmary.

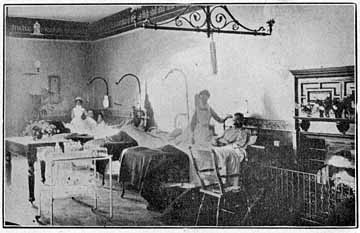

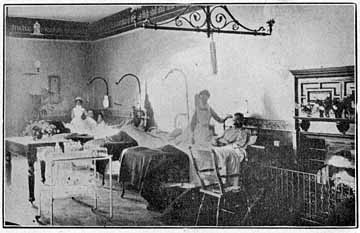

Nevertheless,

it

was

here

that Dr John

Haygarth, a physician

much

in

advance

of

his

time,

who

served

from

1767-1798,

separated

victims

of

infectious

diseases

such

as

small-pox,

typhus

and

cholera

from

non-infectious

cases.

Amazingly,

this

met

with

opposition

by

some

in

the

medical

profession,

who

saw

it

as

an

'unnecessary'

precaution.

However,

segregation

in

spacious,

airy

wards

and

a regime

of

scrupulous

cleanliness

resulted

in

an

immediate

reduction

in

the

death

rate,

and

Dr.

Haygarth's

practices

were

soon

adopted

elsewhere. In

his

pioneering

experiments

he

was

assisted

by

two

heroic

women, Lowry

Thomas and Jane

Bird,

the

first

fever

nurses

on

record. Using

their

improved

methods,

the

dedicated

staff

also

made

great

progress

in

cutting

the

extremely

high

levels

of

mortality

among

new-born

babies.

You can read the whole of Dr Haygarth's fascinating work, How to Prevent the Small-Pox, written in 1785 at the Hathi Trust's website here.

The anonymous author of A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, published in the first years of the nineteenth century, described the Infirmary so: The anonymous author of A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, published in the first years of the nineteenth century, described the Infirmary so:

"The large field on the city side and the open country opposite, render this a fit situation for THE INFIRMARY, which is a handsome pile of building, situate on a pleasant airy spot, on the west side of the city; it was opened on the 17th day of March, 1761, and has been supported by a subscription, and benefactions, that do honour to the city and its environs. The humane attention and care, which the patients receive from the Gentlemen of the faculty, justly entitles them to public thanks. The portrait of Doctor William Stratford, Commissory of the Archdeaconry of Richmond, who was the founder, and left three hundred pounds to the charity, is placed in the council room".

Left: the large area of open ground known anciently as 'Lady Barrow's Hey' and the Infirmary as they appeared on the Chester OS map of 1898. The field may also be seen in the fuzzy photograph below.

Chester

guide

and

author Joseph

Hemingway,

writing

in

1836,

described

the

Infirmary

as "a

most

efficient

establishment

for

the

benevolent

object

for

which

it

was

erected...

it

has

been

the

asylum

and Bethesda of

thousands".

The

records

of

the

years

1755-63

list

the

most

common

ailments

dealt

with

as:

ague,

rheumatism,

fever,

venereal

disease,

abcesses

and

ulcerated

skin,

scurvy,

swollen,

sore

or

painful

limbs,

asthma,

dropsy,

injuries

from

accidents,

consumption

and

tumours.

Also

mentioned

are

hysterical

flatulency,

melancholy,

bloody

flux,

leprosy

and paronchia-

inflammation

of

the

fingernails.

The encouragement of cleanliness

was considered a priority. Paying members of the public were allowed to use the warm slipper bath which was installed at the Infirmary in 1773. The building's enlargement in the 1820s included the provision of two public baths, a free one for dispensary and in-patients and another for paying members of the public- rather wealthy ones, it seems, as admission charges (one shilling in 1811 and two shillings in 1852) excluded all but the wealthiest Cestrians. Both of these offered hot and cold baths, showers and vapour baths.

In 1849, a new complex of washhouses and public baths opened not far away, close to the Water Tower.

In 1790, a sedan chair was purchased in order to transport infirm patients to the Infirmary.

Despite

the

best

efforts

and

high

standards

of

the

Infirmary

staff,

and

Dr.

Haygarth's

pioneering

work,

18th

century

medicine

was

far

from

an

exact

science

and

'private

practitioners'-

often

little

better

than

quacks-

were

common.

The

medicines

themselves

were

of

variable

quality

and

the

local

press

was

full

of

advertisments

for

dubious

remedies,

including Balsam

of

Licorice- "endued

with

the

most

powerful

pectoral,

healing

and

deterging

qualities"- Hill's

Genuine

Ormskirk

Medicine which "infallably

cures

the

bite

of

a mad

dog",

and Dr.

Greenough's

Tincture

for

the

Preservation

of

Teeth. Despite

the

best

efforts

and

high

standards

of

the

Infirmary

staff,

and

Dr.

Haygarth's

pioneering

work,

18th

century

medicine

was

far

from

an

exact

science

and

'private

practitioners'-

often

little

better

than

quacks-

were

common.

The

medicines

themselves

were

of

variable

quality

and

the

local

press

was

full

of

advertisments

for

dubious

remedies,

including Balsam

of

Licorice- "endued

with

the

most

powerful

pectoral,

healing

and

deterging

qualities"- Hill's

Genuine

Ormskirk

Medicine which "infallably

cures

the

bite

of

a mad

dog",

and Dr.

Greenough's

Tincture

for

the

Preservation

of

Teeth.

Nontheless,

Chester

was

also

one

of

the

first

cities

in

the

country

to

persuade

its

citizens-

initially

much

against

their

will-

to

adopt

the

practise

of

general

inoculation,

as

lately

evolved

by Edward

Jenner.

A public

meeting

at

the

Pentice

(forerunner

of

today's

Town

Hall,

formerly

situated

next

to

St. Peter's

Church)

in

March

1778

led

to

the

formation

of

the Smallpox

Society to

promote

inoculation

of

the

entire

population

at

fixed

periods.

Families

where

the

disease

struck

were

encouraged

to

inform

the

Society's

inspector,

Mr

Owen,

at

once

so

by

isolation

neighbours

would have

a better

chance

of

escaping

infection.

Small

monetary

rewards

were

given

to

those

who

co-operated,

and

the

first,

a sum

of

ten

shillings,

went

to

one

Elizabeth

Brierley,

a poor

woman

of

Sty

Lane,

across

the

river

in

Handbridge.

This

Sty

Lane

was

at

the

time

a "pestifirous

slum

warren",

typical

of

the

places

were

smallpox

was

most

likely

to

take

hold.

The

disease

killed

over

sixty

people

on

average

each

year

in

Chester. "Of

these",

declared

the

Society, "58

might

be

saved

if

all

the

rising

generation

were

inoculated

at

the

same

time.

As

things

are,

smallpox

is

spread

by

sufferers

walking

the

streets.

General

inoculation

would

cost

100

guineas

per

year;

lager

sums

have

been

collected

for

the

relief

of

one

family,

or

even

one

person,

at

our

charitable

assemblies".

During the Second World War, Chester itself was not badly bombed but was extensively used as a reception centre for wounded and convalescent servicemen. Large houses in the surrounding countryside such as Saighton Grange and Eaton Hall were transformed into military hospitals or convalescent homes. The Infirmary retained its former role as a general hospital and certainly treated some of the wounded from Dunkirk, and procedures were put into place for the treatment of patients during air raids- During the Second World War, Chester itself was not badly bombed but was extensively used as a reception centre for wounded and convalescent servicemen. Large houses in the surrounding countryside such as Saighton Grange and Eaton Hall were transformed into military hospitals or convalescent homes. The Infirmary retained its former role as a general hospital and certainly treated some of the wounded from Dunkirk, and procedures were put into place for the treatment of patients during air raids-

• Stretcher cases were to be admitted to the City Walls entrance, the Ministry of Health to provide

stretcher-bearers to supplement the porters.

• An open shed was to be erected in the drive opposite the City Walls entrance for decontamination purposes.

• Walking cases were to be admitted to the Bedward Row entrance and treated in 'outpatients'.

• Cases of hysteria were the responsibility of the police and ARP staff and were not to be admitted.

In

front

of

the

Infirmary

entrance

there long stood

a curious

column

on

a worn

sandstone

base.

Dr Haygarth, the

Infirmary's

senior

surgeon,

visited

Ireland

around

1893

and

brought

this

piece

of

the

famous Giant's

Causeway-

an

area

of

volcanic

basalt

formed

by

heat

into

six

and

eight-sided

columns-

back

with

him

as

a souvenir-

seemingly a 'stick

of

rock'

with

a difference!

The

base

upon

which

it

was mounted

was

of

rather

greater

local significance,

being

part

of

the

original

base

of

the

ancient Rood

Cross which

stood

for

centuries

on

the Roodee where

another

section

of

the

base

continues

to

stand.

Correspondant Richard

Edkins tells

us

that "Braun's

map

of

Chester shows

an

enclosure

around

the

Roodeye

Cross.

I recalled

from

a visit

to the Infirmary in

1979

that

the

base

had

the

marks

of

four

iron

railings

set

in

lead.

Were

these

the

marks

of

the

enclosure?

The

Infirmary

staff

knew

nothing

about "that

pile

of

bricks

out

front"

and

were

surprised

by

what

I had

to

say.

I was

disappointed

at

being

unable

to

locate

the

references

in

the

archives

that

year".

Chester guide Joseph Hemingway however,

writing

in

1835,

stated

that,

in

1811,

the

spire

of Holy

Trinity

Church in Watergate

Street, having

become

unsafe,

was

taken

down

and "the

stones

which

formed

the

summit

of

the

spire,

called

the Rose were

placed

by

Dr.

Thackeray

in

the

Infirmary

garden,

as

a pedestal

for

a basaltic

column

from

the

Giant's

Causeway". Chester guide Joseph Hemingway however,

writing

in

1835,

stated

that,

in

1811,

the

spire

of Holy

Trinity

Church in Watergate

Street, having

become

unsafe,

was

taken

down

and "the

stones

which

formed

the

summit

of

the

spire,

called

the Rose were

placed

by

Dr.

Thackeray

in

the

Infirmary

garden,

as

a pedestal

for

a basaltic

column

from

the

Giant's

Causeway".

Upon

visiting

the

site

to

photograph

this

enigmatic

object,

all

this writer found

was

an

indent

in

the

ground

where

it

had

once

stood.

The

staff

at

the

Grosvenor

Museum

and

the

City

Council

conservation

department

were

quite

unable

to

say

what

has

become

of

it,

and

there

the

matter

rested

until

early

May

1998,

when

emiment

local

historian, Len

Morgan,

accidentally

discovered

it-

standing

in

the

grounds

of

the Countess

of

Chester Hospital! "I

was

just

walking

down

the

hospital

corridor,

saw

it

there

and

could

not

believe

it". Just who was responsible for the thoughtful transfer of the relic to its new home remains a mystery. Mr.

Morgan

offered

to

pay

for

a replacement

sundial,

and

suggested

the

provision

of

an information

plaque.

Above,

we

see

a photograph

of

the

'rediscovered'

sundial

in

its

new

location.

The

original

donor, Dr.

Makepiece

Thackeray,

is

buried

in

the

grounds

of Chester

Cathedral,

and

a memorial

plaque

in

his

honour

may

be

seen

there.

Notice

that

the

narrow

road

on

your

right

between

the Queen's

School and

the

hospital

grounds

bears

the

interesting-

and

seemingly

relevant-

name

of Bedward

Row,

which

actually

derives

from Bereward-

a trainer

of

bears.

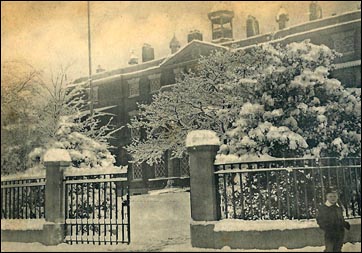

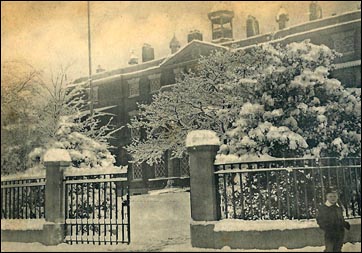

Below

is

a fascinating

view

of

the

infirmary

and

the

Walls

near

it

as

they

appeared

around

the

middle

of

the

19th

century.

Just

beyond

it

you

can

see

the County

Gaol-

built

to

a design by Thomas Harrison to replace

the

medieval Northgate

Gaol,

and

which

stood

here

from

1807-1879

(we learned a little of in our last chapter). Public

executions

were

occasionally

carried

out

on

the

balcony

above

the

main

entrance

and

attracted

large

and

noisy

crowds,

who

gathered

on

the

walls

to

witness

these

events,

often

doubtless

resulting

in

disagreements

with

the

hospital

authorities. Below

is

a fascinating

view

of

the

infirmary

and

the

Walls

near

it

as

they

appeared

around

the

middle

of

the

19th

century.

Just

beyond

it

you

can

see

the County

Gaol-

built

to

a design by Thomas Harrison to replace

the

medieval Northgate

Gaol,

and

which

stood

here

from

1807-1879

(we learned a little of in our last chapter). Public

executions

were

occasionally

carried

out

on

the

balcony

above

the

main

entrance

and

attracted

large

and

noisy

crowds,

who

gathered

on

the

walls

to

witness

these

events,

often

doubtless

resulting

in

disagreements

with

the

hospital

authorities.

Left: the young Queen Elizabeth II visits the Infirmary in 1957.

The

land

upon

which

the

infirmary

stands

was

anciently

known

as Lady

Barrow's

Hey, Hey being

a Saxon

name

for

a field

enclosed

with

hedges. Earlier

still,

the

land

was

used

by

the

Romans

as

a cemetery

and

many

graves

were

uncovered

when

the

hospital

was

being

built

and

enlarged. Chester historian Frank Simpson recorded that, in June 1858, while constructing a railway siding in this field to accomodate exhibitors at the Royal Agricultural Show, the workmen discovered several Roman tombs, which contained such articles as terra-cotta lamps, clay vessels, coins of the period of Domitian, etc.

The City Wall upon which we now stand, to the surprise of many, did not actually exist on this side of the city until the early 12th century- when it was extended by the Normans to enclose this area within the defended circuit. This did not apparently result in any great immediate outburst of urbanisation, however, and most of the great area between the Castle and the North Wall long remained open land- known as The Crofts- and was utilised as smallholdings, gardens and orchards.

In Roman times, the ground on this side of the city west of the present day Inner Ring Road sloped sharply westwards down to the river bank and this slope was eventually cut into three terraces to produce level platforms for buildings and agriculture. The lowest of these terraces was fronted by the massive stone retaining wall which formed the Roman quayside, parts of which may still be seen on the Roodee today. The City Wall was eventually built on top of this lower terrace. The erection of this great wall produced a barrier at the foot of the hillside against which deposits washed down from the slopes above could accumulate, a process that continued from the 12th century right through to fairly recent times. The result is that the entire sloping hillside has disappeared beneath around five metres of accumulated deposits and the ground level we walk on today is now more or less level with the top of the wall. Looking over the parapet opposite the Infirmary at the drop below and the City Wall's great supporting buttresses (clearly visible in the illustration) makes the situation dramatically clear and explains why the walls are so different on this side of the city to those elsewhere in the circuit.

Commencing in the 1150s most of the Crofts came to be occupied by the houses of the religious communities we encountered earlier in our wanderings. Nontheless, much of the land remained unbuilt-upon, serving in its ancient role as the fields and vegetable gardens of the monks and nuns. After the Dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s, their estates were gradually split up and developed- the final section, Lady Barrow's Hey, as late as 1963, when it was occupied by the modern extension to the Infirmary. Commencing in the 1150s most of the Crofts came to be occupied by the houses of the religious communities we encountered earlier in our wanderings. Nontheless, much of the land remained unbuilt-upon, serving in its ancient role as the fields and vegetable gardens of the monks and nuns. After the Dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s, their estates were gradually split up and developed- the final section, Lady Barrow's Hey, as late as 1963, when it was occupied by the modern extension to the Infirmary.

Time

and

again,

during

the

middle

ages

and

in

the

Tudor

and

Stuart

periods-

when

the

port

was

at

its

busiest-

Chester

was

scourged

by

the Bubonic

Plague and

many

of

its

victims

were

interred

here,

as

were

the

many

casualties

of

the

Civil

War

Siege of Chester.

In October 1645, towards the end of the siege, the desperate citizens, labouring under heavy fire, threw up a great earthwork here to defend breaches in the rapidly-crumbling city wall. All available citzens, half-starved though they were, were put to the work, including many women, who helped to carry earth in baskets, even though- as a contemporary account states, "The women, like so many valiant Amazons, do out-face death and dare danger, though it lurk in every basket; seven are shot, three slaine, yet they scorn to leave their matchless undertaking, and thus they continue for ten days' space; possessing the beholders that they are immortal".

The attackers stormed into the breaches but the defences held and they were repulsed with heavy losses. The defenders lost 8 or 10 killed including their leader, Sir William Mainwaring, to whom there is a monument in the Cathedral.

Above we can see the area as it appeared on the 1898 OS map and this remarkable

aerial

view-

a

detail

from John

McGahey's famous View

of

Chester

from

a

Balloon- shows

the

Infirmary

and

its

surroundings

as

they

appeared

around

the

year

1855.

In

July

1998,

the

ugly

modern

buildings

(photographed below)

that

had been erected in 1963 to enlarge

the

18th

century

Infirmary

were

removed,

and,

amidst

the demolition,

a

team

of

Chester's

archaeologists under the direction of Mike Emery undertook

an

investigation

of

the

site.

The

remains

of

some

interesting-

and

previously

unknown-

Roman

and

Saxon

buildings,

a

well-preserved

medieval

road

and

a

17th

century

pipe

kiln-

the

oldest

yet

found

in

Britain-

were

uncovered. Notice

how

these

modern

structures

are

set

into

a

'well'

in

the

ground.

This

method

of

construction

unfortunately

ensured

the

efficient

destruction

of

all

traces

of

ancient

remains. In

July

1998,

the

ugly

modern

buildings

(photographed below)

that

had been erected in 1963 to enlarge

the

18th

century

Infirmary

were

removed,

and,

amidst

the demolition,

a

team

of

Chester's

archaeologists under the direction of Mike Emery undertook

an

investigation

of

the

site.

The

remains

of

some

interesting-

and

previously

unknown-

Roman

and

Saxon

buildings,

a

well-preserved

medieval

road

and

a

17th

century

pipe

kiln-

the

oldest

yet

found

in

Britain-

were

uncovered. Notice

how

these

modern

structures

are

set

into

a

'well'

in

the

ground.

This

method

of

construction

unfortunately

ensured

the

efficient

destruction

of

all

traces

of

ancient

remains.

Right: the Infirmary as it appeared in the mid-1960s; the 1761 building is on the far right and the extensions dating from 1913 closest to the camera. These have now entirely vanished and new housing stands on their site.

(This

writer

made

a

detailed photographic

record

of

the project- including interior studies of the hospital buildings, their demolition, the

archaeologist's

work and the construction of the new houses-

which

is

available

for inspection to

interested

readers).

But

at

least

the

original

1761

Infirmary-

a

grade

II

listed

building-

has

been

fully

restored

to

form

an

integral

part

of

the

new

housing

development,

and

its

interior

sub-divided

into

18

'executive

apartments'.

We

first saw

the

restored building

floodlit

at

night

in

October

2001,

just

after

the

scaffolding

had

come

down,

and

must

say

it

looked

magnificent.

You

can

read

more

about

this

site

and

see

an

'artist's

impression'

of

the

new

houses

which

have

been

built

there-

when

we

reach St. Martin's

Gate. In addition, here is an illustrated history of the hospitals in and around Chester and here is a fascinating short British Pathé newsreel from 1939 of the Bishop of Chester, Doctor Fisher, helping to carry a barrel organ through the streets, aided by others and playing the instrument to raise money for the infirmary. This film records the visit to Chester of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip in 1957 and, as well as scenes such as the opening of County Hall, includes a short sequence of them touring the Infirmary.

• Reader Wilf Burgess wrote to tell us, "I am a retired nurse teacher attempting to find personal recollections of nurses who trained and worked in Chester, particularly at the Chester Royal Infirmary from 1920 onward. My current interest is because I am developing a website about the history of our Schools of Nursing- Chester will be a center piece. But of course the real history can only come from the personal experience of people who were there in some role- nurses or patients. I just hope that some will assist. Any contributions will be gratefully received". • Reader Wilf Burgess wrote to tell us, "I am a retired nurse teacher attempting to find personal recollections of nurses who trained and worked in Chester, particularly at the Chester Royal Infirmary from 1920 onward. My current interest is because I am developing a website about the history of our Schools of Nursing- Chester will be a center piece. But of course the real history can only come from the personal experience of people who were there in some role- nurses or patients. I just hope that some will assist. Any contributions will be gratefully received".

If you can assist Wilf, email him.

Moving

on,

we

see

the

roadway

curving

round

sharply

to

the

right.

Before

the

coming

of

the

Inner

Ringroad

in

the

1960s,

this

was

the

commencement

of Water

Tower

Street,

which

ran

the

full

length

of

the

North

Wall

as

far

as

the Northgate.

Since

being

cut

in

two

by

St.

Martin's

Way,

this

section

has

been

counted

as

forming

part

of City

Walls

Road.

The

footpath

at

this

point

temporarily

parts

company

with

the

road

and

continues

straight

on

up

a

slight

incline-

the

course

we

will

now

be

taking.

The Railway

As

we

proceeded

along

the

side

of

the Roodee,

you

may

have

heard

the

sound

of

passing

trains

and

saw

the

long

line

of

arches

forming

the

railway

viaduct

approaching

closer

and

closer

until,

as

we

enter

this

slight

incline

in

the

wall,

we

see

to

our

surprise

the

railway

line

passing

right

beneath

us!

As

we

look

to

our

right,

we

see

it

cut

through

the

facing

corner

of

the

walls

before

making

its

way

between

North

Wales

and

Chester

Station

and

beyond. As

we

proceeded

along

the

side

of

the Roodee,

you

may

have

heard

the

sound

of

passing

trains

and

saw

the

long

line

of

arches

forming

the

railway

viaduct

approaching

closer

and

closer

until,

as

we

enter

this

slight

incline

in

the

wall,

we

see

to

our

surprise

the

railway

line

passing

right

beneath

us!

As

we

look

to

our

right,

we

see

it

cut

through

the

facing

corner

of

the

walls

before

making

its

way

between

North

Wales

and

Chester

Station

and

beyond.

Thomas

Hughes,

in

his Stranger's

Handbook

to

Chester,

published

in

1856,

wrote, "We

are

now

upon

a

flat

iron

bridge,

and

whew!

with

a

rush

like

that

of

a

tiger

from

his

den,

the

giant

of

the

nineteenth

century-

a

steam

engine

and

train-

emerge

from

the

dark

tunnel

which

passes

under

the

city,

and

dash

away

beneath

us,

full

fourty

miles

an

hour,

en

route to

Ireland,

by

way

of

Holyhead.

The

Roman

walls,

that

resisted

so

successfully

the

Roundhead

batteries,

have

in

our

own

time

succumbed

to

the

engines

of

peace,

and

the

railway

trains,

with

their

living

freight,

now

career

it

merrily

through

two

neighbouring

apertures

in

these

ancient

fortifications".

The

line

had

been

constructed

just

ten

years

earlier,

in

1846,

originally

to

run

between

Chester

and

Ruabon,

and

to

this

day

is

the

main

line

into

North

Wales.

We

will

learn

a

little

more

of

Chester's

railways

in

our

next

chapter. Our

photograph

clearly

shows

the

right-angle

of

the

wall,

the

further

section

a

slender

elevated

walkway-

though

it

seemed

very

solid

and

wall-like

when

we

passed

over

it-

with

the

railway

lines

passing

beneath...

Here is our growing gallery of old photographs of the Chester Royal Infirmary.

We

have

now arrived

at

the

north west

corner

of

the

City

Walls

and

here

encounter

a

couple

of

very

remarkable

old towers...

Curiosities from Chester's History no. 24

1732 The River Dee Company formed by Mr Nathaniel Kinderley and others. A new channel was cut which reclaimed land on the eastern margin of the river. 1732 The River Dee Company formed by Mr Nathaniel Kinderley and others. A new channel was cut which reclaimed land on the eastern margin of the river.

- 1736 By an Act of Parliament, the New River was cut through a large area of white sand- the old course of the Dee by now being so choked up that no vessels could approach within four miles of the city.

- 1741 George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) stayed at the Golden Falcon in Northgate Street on his way to Ireland, and conducted rehersals of his new (and now best-known) work, Messiah.

- 1745 Charles Edward Stuart, the 'Young Pretender' lands in Scotland and defeats English army at Prestonpans; marches south but is forced to retreat at Derby. Fears that the Stuart rebels marching under 'Bonnie Prince Charlie' might attack Chester led to many precautions being taken: the Watergate, Northgate and Sally-Ports walled up, several buildings ajoining the walls were pulled down, and householders were ordered to buy in 2 week's provisions, in case of siege. Great panic ensued, but the city was by-passed by the rebels, who marched on into Staffordshire. When Charles retreated with his army, a large number of these rebels were "brought in 16 carts prisoners to the Castle, which being thus filled, the Spring Assizes were held at Flookersbrook (close to where these words are being written), and "the whole of the court's time was devoted to their trial".

- 1746 The 'Young Pretender' wins a victory at Falkirk but is finally defeated at Culloden; with the help of Flora MacDonald he escapes to France. The wearing of tartan is forbidden throughout Great Britain.

- 1750 Two Irishmen, Garrat Delaney and Edward Johnson, were, upon the evidence of their accomplice, John Caffery, executed at Boughton and gibbetted (hung in chains) on the Parkgate Road for the murder and robbery of their companion, Brian Molloy, "which, it is to be hoped, will be a terror and warning to their countrymen, who have of late committed many villianies in that part of the County". Also at the Assizes, John Ketle, for feloniously driving away three sheep, the property of

Sir Henry Mainwaring Bart., received the sentence of death but was reprieved before the Judge left the city, in order for transportation. Also John Looker and Richard Looker, two brothers, for stealing several silver spoons, were ordered for transportation.

- 1752 Great Britain adopts the Gregorian

calendar on Sept 14th (Sept 3-13th were omitted, leading to riots by people

believing they had been robbed of ten days)

- 1754 The Mayor of Chester, Dr Cowper, refused to take part in the Bull Bait at the High Cross, and ordered the Corporation to do likewise. He also cancelled the Venison Feasts- at which up to 40 haunches may be consumed- previously enjoyed by them. The 'New Cut' of the River Dee from Parkgate to Chester completed. Building of nos 3-11 Abbey Square commenced.

- 1755 The Infirmary (see above) was founded this year, initially housed in the Bluecoat School. The Lisbon earthquake kills 30,000 people

- 1760 King George II dies; succeeded by his grandson George III (1738-1820). Kew Gardens in London opened.

- 1761 The Infirmary (see above) in City Walls Road was built. The Bridgewater Canal, between Liverpool and Leeds, was opened.

- 1762 This year, a "new machine" with "six able horses" would depart from the Golden Talbot (now the Grosvenor Hotel in Eastgate Street) for the Woodside boat house (Birkenhead) on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays at 8am, returning the same day at 4pm.

|

ontinuing

our

stroll

along

City

Walls

Road,

we

soon

come

to

the

distinctive

buildings

of

the former Chester

Royal

Infirmary.

ontinuing

our

stroll

along

City

Walls

Road,

we

soon

come

to

the

distinctive

buildings

of

the former Chester

Royal

Infirmary. The

original

medical

staff

comprised

three

physicians

and

three

surgeons.

A

board

of

governors

was

responsible

for

the

admission

and

discharge

of

patients,

and

they

were

also

responsible

for

administration.

The

medical

staff

themselves

also

served

as

governors.

The

original

medical

staff

comprised

three

physicians

and

three

surgeons.

A

board

of

governors

was

responsible

for

the

admission

and

discharge

of

patients,

and

they

were

also

responsible

for

administration.

The

medical

staff

themselves

also

served

as

governors.  In

Chester itself,

167

subscribers

annually

contributed £288 17s

and

in

the

countryside

43

contributed

£15 4s.

In

North

Wales,

28

people

gave

£73

and

four

subscribers

from

other

surrounding

areas

gave twelve

guineas (£12 12s).

In

Chester itself,

167

subscribers

annually

contributed £288 17s

and

in

the

countryside

43

contributed

£15 4s.

In

North

Wales,

28

people

gave

£73

and

four

subscribers

from

other

surrounding

areas

gave twelve

guineas (£12 12s). As

we

proceeded

along

the

side

of

the Roodee,

you

may

have

heard

the

sound

of

passing

trains

and

saw

the

long

line

of

arches

forming

the

railway

viaduct

approaching

closer

and

closer

until,

as

we

enter

this

slight

incline

in

the

wall,

we

see

to

our

surprise

the

railway

line

passing

right

beneath

us!

As

we

look

to

our

right,

we

see

it

cut

through

the

facing

corner

of

the

walls

before

making

its

way

between

North

Wales

and

Chester

Station

and

beyond.

As

we

proceeded

along

the

side

of

the Roodee,

you

may

have

heard

the

sound

of

passing

trains

and

saw

the

long

line

of

arches

forming

the

railway

viaduct

approaching

closer

and

closer

until,

as

we

enter

this

slight

incline

in

the

wall,

we

see

to

our

surprise

the

railway

line

passing

right

beneath

us!

As

we

look

to

our

right,

we

see

it

cut

through

the

facing

corner

of

the

walls

before

making

its

way

between

North

Wales

and

Chester

Station

and

beyond.

Despite

the

best

efforts

and

high

standards

of

the

Infirmary

staff,

and

Dr.

Haygarth's

pioneering

work,

18th

century

medicine

was

far

from

an

exact

science

and

'private

practitioners'-

often

little

better

than

quacks-

were

common.

The

medicines

themselves

were

of

variable

quality

and

the

local

press

was

full

of

advertisments

for

dubious

remedies,

including Balsam

of

Licorice- "endued

with

the

most

powerful

pectoral,

healing

and

deterging

qualities"- Hill's

Genuine

Ormskirk

Medicine which "infallably

cures

the

bite

of

a mad

dog",

and Dr.

Greenough's

Tincture

for

the

Preservation

of

Teeth.

Despite

the

best

efforts

and

high

standards

of

the

Infirmary

staff,

and

Dr.

Haygarth's

pioneering

work,

18th

century

medicine

was

far

from

an

exact

science

and

'private

practitioners'-

often

little

better

than

quacks-

were

common.

The

medicines

themselves

were

of

variable

quality

and

the

local

press

was

full

of

advertisments

for

dubious

remedies,

including Balsam

of

Licorice- "endued

with

the

most

powerful

pectoral,

healing

and

deterging

qualities"- Hill's

Genuine

Ormskirk

Medicine which "infallably

cures

the

bite

of

a mad

dog",

and Dr.

Greenough's

Tincture

for

the

Preservation

of

Teeth. During the Second World War, Chester itself was not badly bombed but was extensively used as a reception centre for wounded and convalescent servicemen. Large houses in the surrounding countryside such as Saighton Grange and Eaton Hall were transformed into military hospitals or convalescent homes. The Infirmary retained its former role as a general hospital and certainly treated some of the wounded from Dunkirk, and procedures were put into place for the treatment of patients during air raids-

During the Second World War, Chester itself was not badly bombed but was extensively used as a reception centre for wounded and convalescent servicemen. Large houses in the surrounding countryside such as Saighton Grange and Eaton Hall were transformed into military hospitals or convalescent homes. The Infirmary retained its former role as a general hospital and certainly treated some of the wounded from Dunkirk, and procedures were put into place for the treatment of patients during air raids- Chester guide Joseph Hemingway however,

writing

in

1835,

stated

that,

in

1811,

the

spire

of Holy

Trinity

Church in

Chester guide Joseph Hemingway however,

writing

in

1835,

stated

that,

in

1811,

the

spire

of Holy

Trinity

Church in  Below

is

a fascinating

view

of

the

infirmary

and

the

Walls

near

it

as

they

appeared

around

the

middle

of

the

19th

century.

Just

beyond

it

you

can

see

the County

Gaol-

built

to

a design by Thomas Harrison to replace

the

medieval

Below

is

a fascinating

view

of

the

infirmary

and

the

Walls

near

it

as

they

appeared

around

the

middle

of

the

19th

century.

Just

beyond

it

you

can

see

the County

Gaol-

built

to

a design by Thomas Harrison to replace

the

medieval  Commencing in the 1150s most of the Crofts came to be occupied by the houses of the religious communities we encountered earlier in our wanderings. Nontheless, much of the land remained unbuilt-upon, serving in its ancient role as the fields and vegetable gardens of the monks and nuns. After the Dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s, their estates were gradually split up and developed- the final section, Lady Barrow's Hey, as late as 1963, when it was occupied by the modern extension to the Infirmary.

Commencing in the 1150s most of the Crofts came to be occupied by the houses of the religious communities we encountered earlier in our wanderings. Nontheless, much of the land remained unbuilt-upon, serving in its ancient role as the fields and vegetable gardens of the monks and nuns. After the Dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s, their estates were gradually split up and developed- the final section, Lady Barrow's Hey, as late as 1963, when it was occupied by the modern extension to the Infirmary. In

July

1998,

the

ugly

modern

buildings

(photographed below)

that

had been erected in 1963 to enlarge

the

18th

century

Infirmary

were

removed,

and,

amidst

the

In

July

1998,

the

ugly

modern

buildings

(photographed below)

that

had been erected in 1963 to enlarge

the

18th

century

Infirmary

were

removed,

and,

amidst

the  • Reader Wilf Burgess wrote to tell us, "I am a retired nurse teacher attempting to find personal recollections of nurses who trained and worked in Chester, particularly at the Chester Royal Infirmary from 1920 onward. My current interest is because I am developing a website about the history of our Schools of Nursing- Chester will be a center piece. But of course the real history can only come from the personal experience of people who were there in some role- nurses or patients. I just hope that some will assist. Any contributions will be gratefully received".

• Reader Wilf Burgess wrote to tell us, "I am a retired nurse teacher attempting to find personal recollections of nurses who trained and worked in Chester, particularly at the Chester Royal Infirmary from 1920 onward. My current interest is because I am developing a website about the history of our Schools of Nursing- Chester will be a center piece. But of course the real history can only come from the personal experience of people who were there in some role- nurses or patients. I just hope that some will assist. Any contributions will be gratefully received".