s

we leave the Old Dee Bridge and the roar of the weir behind us, we come

to a section of Chester's ancient city walls that has undergone considerable

changes over the centuries.

s

we leave the Old Dee Bridge and the roar of the weir behind us, we come

to a section of Chester's ancient city walls that has undergone considerable

changes over the centuries.

Without doubt this piece of high ground round which the River Dee sweeps in

a gradual curve has had strategic importance from earliest times, and around

the year 907AD, the Saxons of Mercia under Aethelfleda, as part of

their re-occupation of the old Roman fortress, erected a fortified base here

and incorporated it into their extension to the walls, to serve as part of

their defences against the Danes, then being driven out of Ireland and looking

for new lands to occupy.

Of

this

Saxon

fortress

no

trace

remains

and

very

little

more

is

known

of

the

site

until

the

winter

of

1069-70,

when

the

army

of Duke

William

of

Normandy came

to

Saxon

Chester,

which

became

the

last

remaining

great

town

in

England

to

fall

to

the

Conqueror's

sword

during

the

final

stages

of

the Harrying

of

the

North in

1069-70,

fully

three

years

after

the

Battle

of

Hastings.

Numerous rumours had long been circulating among the Norman army about the

bad roads, the position of the city- surrounded as it was by thick forests

and treacherous swamps- of its numerous inhabitants- and of their obstinate

courage and deadly familiarity with the longbow. Many of William's nobles, worn out by the struggles in the North,

and alarmed at these stories, demanded their discharge. Some actually retired

to Normandy, abandoning the lands with which they had already been rewarded;

but the persuasive powers of Duke William prevailed- he promised them great

rewards, and, as the conquest of Chester was the last of his projects, that

they would find rest after this one final victory.

As it turned out, as the Norman army prevailed. The death toll during the campaign is believed to have been around 150,000, with substantial social, cultural, and economic damage. Due to the ruthless and violent "scorched earth" policy which the Normans employed, much of the land was laid waste and depopulated. In parts of the north, the damage was such that the survivors had to resort to cannibalism. Inevitably, plague followed. All told, about a fifth of the population of England may have died during the Norman Conquest. We know little about the battle for Chester or the number of casualties involved but we do know that a very large proportion of the houses in the town were destroyed.

As it turned out, as the Norman army prevailed. The death toll during the campaign is believed to have been around 150,000, with substantial social, cultural, and economic damage. Due to the ruthless and violent "scorched earth" policy which the Normans employed, much of the land was laid waste and depopulated. In parts of the north, the damage was such that the survivors had to resort to cannibalism. Inevitably, plague followed. All told, about a fifth of the population of England may have died during the Norman Conquest. We know little about the battle for Chester or the number of casualties involved but we do know that a very large proportion of the houses in the town were destroyed.

William

granted

the

Earldom

of

Chester

first

to Walter

de

Gherbaud-

who,

however

soon

returned

to

an easy life in Normandy-

and

then

to

his

nephew, Hugh

D'Avranches-

know

as Lupus (the

wolf)

but

in

later

life,

especially

by

the

Welsh,

as Hugh

Vras (Hugh the Fat) - "To

hold

to

him

and

his

heirs

as

freely

by

the

sword

as

the

King

holds

the

Crown

of

England".

The

Earldom

became

very

powerful

and

virtually

independent

of

the

Crown,

the

Earl

having

his

own

Parliament

consisting

of

eight

of

his

chosen

Barons

and

their

tenants,

and

they

were

in

no

way

bound

by

any

laws

passed

by

the

English

Parliament

with

the

exception

of

that

of

treason.

Hugh erected a typical Norman timber motte and bailey castle here which was

soon rebuilt in enduring stone. Of the fate of the Saxon stronghold formerly occupying

the site we know nothing at all, but its Norman successor over the course

of centuries grew into a formidable defensive structure of great strategic

importance.

Hugh erected a typical Norman timber motte and bailey castle here which was

soon rebuilt in enduring stone. Of the fate of the Saxon stronghold formerly occupying

the site we know nothing at all, but its Norman successor over the course

of centuries grew into a formidable defensive structure of great strategic

importance.

Following the Crown's annexation of the Earldom of Chester in 1237, when the

last Norman Earl died without issue, considerable enlargement and strengthening

were carried out by Henry III and Edward I, particularly in the outer bailey,

where the pallisade was replaced by a great stone wall in 1247-51.

Chester

Castle

was

the

frontier

base

from

which

North

Wales

was

attacked

and

eventually

conquered

in

the

12th

and

13th

centuries

and

the

exchequer,

courts

and

prison

were

based

here,

as

well

as

housing

the

garrison.

In 1246, Owen ap Gruffydd (Owain Gwynneth) escaped from imprisonment here to join his

brother Llewelyn in the fight against the English, under whose leadership

in 1257 they "ravaged the country to the very gates of the city".

In 1276-7 Edward came twice to Chester to summon Llewellyn to make peace,

but was each time refused, on the grounds that the Prince of Wales "feared

for his safety", whereupon the King laid siege to Rhuddlan Castle, where Llewellyn

was starved into submission.

In

1397,

it

is

recorded

that

the

Deputy

Constable

of

Chester Castle,

Thomas

le

Wodeward,

took

delivery

of

certain

new

supplies:

• 11 iron collars and 2 gross of iron chain.

• 2 pairs of iron belts with shackles

• 2 pairs of iron handcuffs with 4 iron shackles

• 7 pairs of iron feet fetters with 3 shackles

• 1 hasp for the stocks

In 1399 Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Lancaster, took Chester, soon after

mustering his troops under the walls and marching against Richard II, whom

he took at Flint Castle. He returned to Chester with the unfortunate monarch

(dressed in the monk's robe in which he had attempted to escape) and the Earl

of Salisbury "mounted on two little white nagges not worth 40 francs" and

lodged them in the Castle. After resting in a tower over the outer gateway,

they were escorted to Westminster. Bolingbroke deposed Richard- who was murdered

in prison the following year- and was elected King Henry IV by Parliament.

In 1399 Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Lancaster, took Chester, soon after

mustering his troops under the walls and marching against Richard II, whom

he took at Flint Castle. He returned to Chester with the unfortunate monarch

(dressed in the monk's robe in which he had attempted to escape) and the Earl

of Salisbury "mounted on two little white nagges not worth 40 francs" and

lodged them in the Castle. After resting in a tower over the outer gateway,

they were escorted to Westminster. Bolingbroke deposed Richard- who was murdered

in prison the following year- and was elected King Henry IV by Parliament.

These

great

events

were,

of

course,

immortalised

by

Shakespeare,

and John

Speed commented

of

Richard, "If

to

spare

his

people's

bloud

he

was

contented

so

tamely

to

quit

his

royall

right,

this

fact

doth

not

only

seeme

excusable,

but

glorious;

but

men

rather

think

that

it

was

sloth,

and

a

vaine

trust

in

dissimulation

which

his

enemies

had

long

since

discovered

in

him".

After

centuries

of

service

(from

the

Saxons

to

the

20th

century

Edwardians,

architects

built

for

ever,

not

for

mere

decades

as

now)

Chester

Castle

sustained

serious

damage

during

the

Civil

War,

and

by

the

18th

century

had

been

allowed

to

fall

into

a

state

of

advanced

decay.

After

the

war, Oliver

Cromwell had

ordered

many

castles-

such

as

that

at

nearby Liverpool-

to

be

partially

or

completely

demolished

so

they

could

not

be

used

to

wage

war

again,

but

here

at

Chester

the

least

damaged

parts

of

the

building

continued

in

use;

writing

of

Chester

Castle

in

the Vale

Royal

of

England in

1651, Daniel

King recorded

that, "The

castle

is

a

place

having

priviledge

of

itself,

and

hath

a

Constable...

At

the

first

coming

in

is

the

Gate-house,

which

is

a

prison

for

the

whole

County,

having

divers

rooms

and

lodgings.

And

hard

within

the

Gate

is

a

house,

which

was

sometime

the Exchequer but

now

the Custom

House. Not

far

from

thence

in

the

Base

Court

is

a

deep

well,

and thereby

stables,

and

other

Houses

of

Office.

On

the

left-hand

is

a

chappell;

and

hard

by

adjoyning

thereunto,

the

goodly

fair

and

large

Shire-Hall

newly

repaired;

where

all

matters

of

Law

touching

the County

Palatine are

heard,

and

judicially

determined.

And

at

the

end

thereof

the

brave New

Exchequer,

for

the

said County

Palatine. All

these

are

in

the

Base

Court. Then

there

is

a

Draw-Bridge

into

the

Inner

Ward,

wherein

are

divers

goodly

Lodgings

for

the

Justices,

when

they

come:

And

herein

the

Constable

himself

dwelleth. The

Thieves

and

Fellons

are

arraigned

in

the

said

Shire-Hall;

and,

being

condemned,

are

by

the

Constable

of

the

Castle,

or

his

Deputy,

delivered

to

the

Sheriffs

of

the

City,

a

certain

distance

without

the

Castle-Gate,

at

a

stone

called The

Glovers

Stone from

which

place,

the

said

Sheriffs

convey

them

to

the

place

of

execution,

called Boughton"

After

the

war, Oliver

Cromwell had

ordered

many

castles-

such

as

that

at

nearby Liverpool-

to

be

partially

or

completely

demolished

so

they

could

not

be

used

to

wage

war

again,

but

here

at

Chester

the

least

damaged

parts

of

the

building

continued

in

use;

writing

of

Chester

Castle

in

the Vale

Royal

of

England in

1651, Daniel

King recorded

that, "The

castle

is

a

place

having

priviledge

of

itself,

and

hath

a

Constable...

At

the

first

coming

in

is

the

Gate-house,

which

is

a

prison

for

the

whole

County,

having

divers

rooms

and

lodgings.

And

hard

within

the

Gate

is

a

house,

which

was

sometime

the Exchequer but

now

the Custom

House. Not

far

from

thence

in

the

Base

Court

is

a

deep

well,

and thereby

stables,

and

other

Houses

of

Office.

On

the

left-hand

is

a

chappell;

and

hard

by

adjoyning

thereunto,

the

goodly

fair

and

large

Shire-Hall

newly

repaired;

where

all

matters

of

Law

touching

the County

Palatine are

heard,

and

judicially

determined.

And

at

the

end

thereof

the

brave New

Exchequer,

for

the

said County

Palatine. All

these

are

in

the

Base

Court. Then

there

is

a

Draw-Bridge

into

the

Inner

Ward,

wherein

are

divers

goodly

Lodgings

for

the

Justices,

when

they

come:

And

herein

the

Constable

himself

dwelleth. The

Thieves

and

Fellons

are

arraigned

in

the

said

Shire-Hall;

and,

being

condemned,

are

by

the

Constable

of

the

Castle,

or

his

Deputy,

delivered

to

the

Sheriffs

of

the

City,

a

certain

distance

without

the

Castle-Gate,

at

a

stone

called The

Glovers

Stone from

which

place,

the

said

Sheriffs

convey

them

to

the

place

of

execution,

called Boughton"

Another

source

records

that

that

criminals

were

handed

over "at Glovers

Stoune to

such

officer

of

the

Cittie

of

Chester,

in

and

from

hence

to

whipp

them

through

the

Cittie".

In

the

years

since,

what is conjectured to be the

old

Glovers Stone

which

long

marked

the

boundary

of

this

'no-man's-land'

between

the

authorities

of

Crown

and

City

outside

the

Castle

gateway

was

moved

to

a

small

garden

area

under

the

city

walls

and

close

to

the Watertower,

where

it

may

still

be

seen

today.

In

the

years

since,

what is conjectured to be the

old

Glovers Stone

which

long

marked

the

boundary

of

this

'no-man's-land'

between

the

authorities

of

Crown

and

City

outside

the

Castle

gateway

was

moved

to

a

small

garden

area

under

the

city

walls

and

close

to

the Watertower,

where

it

may

still

be

seen

today.

In

1696,

a

mint

was

set

up

at

Chester

Castle.

This

was

part

of

an

effort

to

completely

renew

the

nation's

currency,

and

the

man

in

charge

in

London

was

one Isaac

Newton (later

knighted

for

these

efforts,

but

not

for

his

science).

To

take

charge

of

the

Chester

mint

he

appointed

the

great

astronomer Edmund

Halley (he

of

comet

fame),

who

spent

two

years

here.

The

site

of

the

mint

is

marked

on

signs

put

up

by

English

Heritage,

just

behind

the

Half

Moon

Tower-

and

you

can

read

some

of

Halley's

reminisciences

of

his

time

in

Chester here.

Today,

incidentally,

Britain's

currency-

and

also

the

coinage

and

banknotes

of

many

other

countries-

is

produced

at

only

one

location,

the

Royal

Mint

at

Pontyclun,

South

Wales.

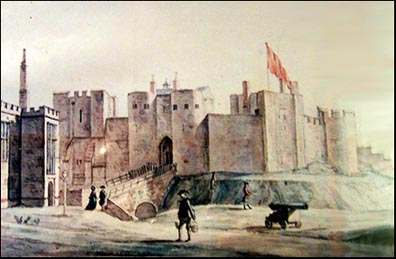

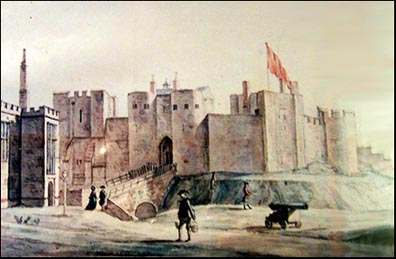

The

two watercolours

above

by Moses

Griffith (1747-1819)

shows

Chester

Castle

as

it

appeared

around

1750,

thirty-odd

years

before

its

almost

total

demolition

and

rebuilding-

as

does

the

fine

modern

drawing

higher up the page

by David

Vale.

When

we

view

the

magnificent

remains

of Conwy

Castle and

the

other

great

Edwardian

strongholds

of

neighbouring

North

Wales,

it

is

easy

to

feel

a

great

regret

that

more

of

the

ancient

fabric

of

Chester

Castle

was

not

allowed

to

survive

to

the

present

day.

In

the

illustration,

you

can

see

across

the

outer

bailey

to

the

great

outer

gateway,

built

around

1292,

whose

two

tall

half-drum

towers

flanked

a

drawbridge

across

a

moat

cut

more

than

eight

metres

below

the

modern

surface. On

the

left

is

the

Great

Hall

or Shire

Hall of

1250-3

(rebuilt

in

1579-81)

which

housed

the

courts

of

the

justices

of

the

county

and

at

its

south

end

was

located

the

Exchequer

Court

of

the

County

Palatine

of

Chester.

It

was

here,

on

3rd

February

1646

that

the

citizens

of

Chester

completed

the

capitulation

of

their

city

to

Parliament

after

a

long

and

bloody

siege.

In

the

illustration,

you

can

see

across

the

outer

bailey

to

the

great

outer

gateway,

built

around

1292,

whose

two

tall

half-drum

towers

flanked

a

drawbridge

across

a

moat

cut

more

than

eight

metres

below

the

modern

surface. On

the

left

is

the

Great

Hall

or Shire

Hall of

1250-3

(rebuilt

in

1579-81)

which

housed

the

courts

of

the

justices

of

the

county

and

at

its

south

end

was

located

the

Exchequer

Court

of

the

County

Palatine

of

Chester.

It

was

here,

on

3rd

February

1646

that

the

citizens

of

Chester

completed

the

capitulation

of

their

city

to

Parliament

after

a

long

and

bloody

siege.

Right: Chester Castle as recorded in pen-and-ink in Daniel King's 'Vale Royal of England', 1656, a decade after the end of the Civil War. St. Mary's Church, the old Bridgegate and the now-vanished fortifications on the southern end of the Old Dee Bridge are also clearly visible.

We

can

also

see

the

church

of St. Mary-on-the-Hill (a

Norman

foundation,

rebuilt in the 16th century and restored

by

Harrison

in

1861-2,

and

again

by

Seddon

in

1891)

on

the

far

left

and

above

it

the Old

Dee

Bridge crosses

the

River

Dee,

much

as

it

continues

to

do

to

this

day. The church is also known as St. Mary-Within-the-Walls to distinguish it from

the first church to be built on the other side of the river, St. Mary-Without-the-Walls in Handbridge, whose fine tall spire is clearly visible from all around. Built in 1887, occupying a site of a Roman cemetery, it was a gift to the city from the Duke of Westminster.

St. Mary-Within-the-Walls, however, has a far more reaching history. The original church on the spot, dating from the early 12th century, was known as St. Mary de Castro ('of the Castle'). The porch of present structure contains stones brought from the nunnery of St. Mary's, which once stood overlooking the Roodee where the unsightly Police HQ building is now. The tower was once much lower than it is today- as a precaution against attack it was forbidden for any neighbouring building to overlook the walls of the Castle. The ornately-carved upper parts of the tower we see today were added by the castle's re-builder, Thomas Harrison in the middle of the 19th century. The interior of the church is very fine and boasts a splendid English oak inner roof, brought from Basingwerk Abbey (whose picturesque ruins still survive near Holywell in North Wales) when that establishment was dissolved by the agents of King Henry VIII. Many of Chester's greatest citizens were buried here and some of their monuments are likely to surprise the visitor, being as they are painted in bright colours. The church was deconsecrated in 1972 and today hosts an education centre operated by Cheshire County Council.

St. Mary-Within-the-Walls, however, has a far more reaching history. The original church on the spot, dating from the early 12th century, was known as St. Mary de Castro ('of the Castle'). The porch of present structure contains stones brought from the nunnery of St. Mary's, which once stood overlooking the Roodee where the unsightly Police HQ building is now. The tower was once much lower than it is today- as a precaution against attack it was forbidden for any neighbouring building to overlook the walls of the Castle. The ornately-carved upper parts of the tower we see today were added by the castle's re-builder, Thomas Harrison in the middle of the 19th century. The interior of the church is very fine and boasts a splendid English oak inner roof, brought from Basingwerk Abbey (whose picturesque ruins still survive near Holywell in North Wales) when that establishment was dissolved by the agents of King Henry VIII. Many of Chester's greatest citizens were buried here and some of their monuments are likely to surprise the visitor, being as they are painted in bright colours. The church was deconsecrated in 1972 and today hosts an education centre operated by Cheshire County Council.

In the 18th century, a remarkable event in early avaition history occured at Chester Castle, which was recorded the year after its undertaking by the ‘pilot’, Thomas Baldwin, in his book, AIROPAIDIA: Containing the Narrative of a BALLOON EXCURSION from CHESTER.

He wrote, “On Thursday, the 8th of September, 1785, at six in the morning, one of the cannons (a six-pounder] was first fired in the Castle yard, to inform the city and neighbourhood that the necessary preparations were making to inflate the balloon. At xii the cannon fired a second time, to announce that the process was in a proper degree of forwardness.

Before half-past one, Mr. Lunardi had inflated his balloon in the finest manner; and at 40 minutes past one, the Balloon having a levity which not less than 20 pounds weight would counterpoise, Mr. Baldwin was liberated by the hands of Mr. Lunardi, who suffered no one to approach the car.

The car first landed at 28 minutes past three, in a field belonging to a farm called Bellair, in the Township of Kingsley, near two miles east by south from the Town of Frodsham, and twelve from Chester. He landed exactly at 7 minutes before four, near the middle of Rixton Moss; and on his return to Chester the following day he was met by the Militia Band and ushered with loud huzzas into his native city.”

This historic event took place less than two years after the world's first manned flight, that of the Montgolfier Brothers' balloon in Paris on 21st November 1783.

Around

1780,

100

years

after

the Vale

Royal entry

was

written,

the

old

stones

of

the

medieval

Chester

Castle

were

swept

away

to

make

room

for

the

buildings

we

see

today. This

great

complex

of

Shire

Hall,

courts,

prison,

armoury

and

barracks

was

designed,

after

winning

a

competition-

and

a

prize

of

50

guineas-

by Thomas

Harrison-

then

a

relatively

obscure

architect

with

very

few

buildings

to

his

name-

and

were

erected

between

the

years

1785

and

1822.

Harrison

(1744-1829)

was

born

in

Richmond,

Yorkshire,

the

son

of

a

joiner.

His

early

talent

for

mechanics,

mathematics

and

drawing

won

him

the

patronage

of

a

local

nobleman,

who

sent

him

on

that

essential

experience

in

the

education

of

a

privileged

young

man

of

the

day-

the

Grand

Tour

of

Italy,

where-

despite

having

no

formal

architectural

training-

he

gained

a

reputation

based

upon

his

designs

for

a

number

of

buildings

in

Rome-

although

none

were

actually

built.

Harrison

(1744-1829)

was

born

in

Richmond,

Yorkshire,

the

son

of

a

joiner.

His

early

talent

for

mechanics,

mathematics

and

drawing

won

him

the

patronage

of

a

local

nobleman,

who

sent

him

on

that

essential

experience

in

the

education

of

a

privileged

young

man

of

the

day-

the

Grand

Tour

of

Italy,

where-

despite

having

no

formal

architectural

training-

he

gained

a

reputation

based

upon

his

designs

for

a

number

of

buildings

in

Rome-

although

none

were

actually

built.

Upon

returning

to

England,

Harrison

worked

on

a

few

minor

architectural

commissions

before

winning

the

Chester

competition

at

the

age

of

40.

The

commission

was

originally

just

for

a

new

gaol

(see

next

page)

but

was

later

extended

to

cover

the

rebuilding

of

the

medieval

Shire

Hall-

unfortunately

for

us:

by

all

accounts

it

had

been

a

most

beautiful

and

impressive

building-

and

in

1804,

extended

again

to

include

new

barracks

and

armoury

blocks.

When

completed,

the

complex

covered

a

much

larger

area

than

the

old

Castle,

extending

well

beyond

the

medieval

curtain

walls.

To

complete

his

scheme,

Harrison

designed

an

impressive

new

entrance

in

the

Greek

Doric

style,

which

was

erected

between

1810

and

1822,

a

free-standing

structure

similar

to

Berlin's

famous

Brandenburg

Gate-

built

about

twenty

years

earlier-

and

said

to

be

based

on

the Propylaeum of

the

Acropolis

in

Athens.

The

centre

of

the

new

legal

buildings

was

the Assize

Court with

its

massive

and

impressive

portico.

Each

of

its

twelve

Doric

columns

is

formed

from

one

single

stone

23

feet

in

height.

When

the

first

of

these

was

raised,

with

great

ceremony,

within

a

cavity in

the

plinth

was

placed

a

lead

box,

inside

which

was

a

small

Wedgewood

urn,

this

in

turn

containing

several

coins

of

the

day.

An

engraved

brass

plate

was

fastened

over

the

cavity

before

the

column

was

hauled

into

position.

Due

to

the

court's

foundations

being

situated

over

the

old

moat

of

the

medieval

castle,

considerable

structural

cracking

occured

and

when

in

1920,

major

repairs

were

undertaken,

this

urn

was

found

together

with,

under

another

column,

a

small

brass

snuffbox

which

had

belonged

to

Admiral

Lord

Nelson,

which

also

contained

coins.

When

the

columns

were

re-erected

in

1922,

the

urn

was

replaced in

situ,

coins

dated

1921-22

having

been

added.

The

snuffbox,

however,

was

added

to

the

collection

of

Cheshire

Regimental

relics.

Due

to

the

court's

foundations

being

situated

over

the

old

moat

of

the

medieval

castle,

considerable

structural

cracking

occured

and

when

in

1920,

major

repairs

were

undertaken,

this

urn

was

found

together

with,

under

another

column,

a

small

brass

snuffbox

which

had

belonged

to

Admiral

Lord

Nelson,

which

also

contained

coins.

When

the

columns

were

re-erected

in

1922,

the

urn

was

replaced in

situ,

coins

dated

1921-22

having

been

added.

The

snuffbox,

however,

was

added

to

the

collection

of

Cheshire

Regimental

relics.

The

interior

of

the

court

was

built

in

a

semi-circle

with

twelve

Ionic

columns

as

supports.

Originally,

the

jury's

retiring

room

and

the

turnkey's

lodge

were

to

the

left

of

the

court,

as

was

also

the

entrance

to

the

cells,

the

lower

level

of

which

were

occupied

by

the

felons

and

the

upper

by

the

debtors.

The

upper

cells

survive

today

and

are

used

for

the

daily

housing

of

prisoners

awaiting

appearance

in

what

is

today Chester

Crown

Court.

Many

famous

trials

have

taken

place

here

over

the

years,

none

more

notorious

than

that

of

Brady

and

Hindley,

the

'Moors

Murderers' in 1966.

"Would you have me go to Chester and work there now? I don’t like the thoughts of it. If I go to Chester and work there, I can’t be my own man; I must work under a master, and perhaps he and I should quarrel, and when I quarrel I am apt to hit folks, and those that hit folks are sometimes sent to prison; I don’t like the thought either of going to Chester or to Chester prison. What do you think I could earn at Chester?"

Tinker: "A matter of eleven shillings a week, if anybody would employ you, which I don’t think they would with those hands of yours. But whether they would or not, if you are of a quarrelsome nature you must not go to Chester; you would be in the castle in no time". George Borrow: Lavengro (1851)

| Above left: Thomas Harrison's rebuilt castle as we see it today. Right: what we may still have if the rebuilding had not occured- an amazing recreation by Martin Moss of the medieval castle surrounded by the traffic and structures of modern Chester. The Castle features in another of Martin's works- a remarkable view of Chester from across the River Dee around the year 1750... |

Now

go

on

to part

II of

our

exploration

of

Chester

Castle...

As it turned out, as the Norman army prevailed. The death toll during the campaign is believed to have been around 150,000, with substantial social, cultural, and economic damage. Due to the ruthless and violent "scorched earth" policy which the Normans employed, much of the land was laid waste and depopulated. In parts of the north, the damage was such that the survivors had to resort to cannibalism. Inevitably, plague followed. All told, about a fifth of the population of England may have died during the Norman Conquest. We know little about the battle for Chester or the number of casualties involved but we do know that a very large proportion of the houses in the town were destroyed.

As it turned out, as the Norman army prevailed. The death toll during the campaign is believed to have been around 150,000, with substantial social, cultural, and economic damage. Due to the ruthless and violent "scorched earth" policy which the Normans employed, much of the land was laid waste and depopulated. In parts of the north, the damage was such that the survivors had to resort to cannibalism. Inevitably, plague followed. All told, about a fifth of the population of England may have died during the Norman Conquest. We know little about the battle for Chester or the number of casualties involved but we do know that a very large proportion of the houses in the town were destroyed. Hugh erected a typical Norman timber

Hugh erected a typical Norman timber  In 1399

In 1399  After

the

war,

After

the

war,

In

the

illustration,

you

can

see

across

the

outer

bailey

to

the

great

outer

gateway,

built

around

1292,

whose

two

tall

half-drum

towers

flanked

a

drawbridge

across

a

moat

cut

more

than

eight

metres

below

the

modern

surface. On

the

left

is

the

Great

Hall

or Shire

Hall of

1250-3

(rebuilt

in

1579-81)

which

housed

the

courts

of

the

justices

of

the

county

and

at

its

south

end

was

located

the

Exchequer

Court

of

the

County

Palatine

of

Chester.

It

was

here,

on

3rd

February

1646

that

the

citizens

of

Chester

completed

the

capitulation

of

their

city

to

Parliament

after

a

long

and

bloody

siege.

In

the

illustration,

you

can

see

across

the

outer

bailey

to

the

great

outer

gateway,

built

around

1292,

whose

two

tall

half-drum

towers

flanked

a

drawbridge

across

a

moat

cut

more

than

eight

metres

below

the

modern

surface. On

the

left

is

the

Great

Hall

or Shire

Hall of

1250-3

(rebuilt

in

1579-81)

which

housed

the

courts

of

the

justices

of

the

county

and

at

its

south

end

was

located

the

Exchequer

Court

of

the

County

Palatine

of

Chester.

It

was

here,

on

3rd

February

1646

that

the

citizens

of

Chester

completed

the

capitulation

of

their

city

to

Parliament

after

a

long

and

bloody

siege. Harrison

(1744-1829)

was

born

in

Richmond,

Yorkshire,

the

son

of

a

joiner.

His

early

talent

for

mechanics,

mathematics

and

drawing

won

him

the

patronage

of

a

local

nobleman,

who

sent

him

on

that

essential

experience

in

the

education

of

a

privileged

young

man

of

the

day-

the

Grand

Tour

of

Italy,

where-

despite

having

no

formal

architectural

training-

he

gained

a

reputation

based

upon

his

designs

for

a

number

of

buildings

in

Rome-

although

none

were

actually

built.

Harrison

(1744-1829)

was

born

in

Richmond,

Yorkshire,

the

son

of

a

joiner.

His

early

talent

for

mechanics,

mathematics

and

drawing

won

him

the

patronage

of

a

local

nobleman,

who

sent

him

on

that

essential

experience

in

the

education

of

a

privileged

young

man

of

the

day-

the

Grand

Tour

of

Italy,

where-

despite

having

no

formal

architectural

training-

he

gained

a

reputation

based

upon

his

designs

for

a

number

of

buildings

in

Rome-

although

none

were

actually

built.